There’s an undeniable feeling of building anticipation during the long drive to the Jurassic Mile, the dinosaur excavation underway in the northern Bighorn Basin near Cowley.

As vehicles churn up clouds of red and tan dust, the excitement is palpable for first-time paleontologists eager to get their hands dirty.

The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis’s (CMI) Family Dino Dig isn’t babysitting in a sand pit with plastic bones.

Participants work alongside paleontologists and make their own discoveries and lifelong memories as they brush and poke into the 145-million-year-old mud where buried treasures can be found.

“We want kids and families to experience the real science,” said Melissa Trumpey, the director of public events and family programs at CMI. “We love having them out here, doing real science with authentic fossils. We’ve been out here since 2018, and we’ve had Family Dino Digs every year since.”

A Lay Of The Land

After a hearty breakfast, a chauffeured ride to the Jurassic Mile with Trumpey, and the all-important safety presentation (snakes and sun are dangerous and should be avoided when possible), the Family Dino Dig starts with a “geology lecture,” courtesy of Joseph Frederickson, the lead paleontologist and manager of the CMI’s Natural Science Collection.

Instead of whiteboards and PowerPoint presentations, “Dr. Joe’s” classroom requires a short ascent to the high point of the Jurassic Mile. From this spot, the gorgeous geology of the Bighorn Basin stretches out in every direction, a tapestry of color and opportunity.

“Rocks are usually laid down horizontally, like pieces of paper – flat,” Frederickson told the latest group of Family Dino Dig participants. “All of this rock that you see here is not flat. It has been pushed together. When mountains uplift, they contract a little bit, pushing that rock together, just like pushing on two ends of a piece of paper.”

From this spot, Peterson can point out the rusted red rock of the Chugwater Formation, the scrubby escarpments that were once the bottom of the Sundance Sea, and the blocky sandstone of the Cloverly Formation that kept the dinosaurs right where they were originally buried.

The participants are unknowingly standing on the spot where they’ll find dinosaurs. Frederickson's classroom is the Upper Sauropod Quarry, an exposure in the Morrison Formation where CMI paleontologists excavated one of the two long-necked dinosaurs mounted in the Dinosphere, a former IMAX theater that was retrofitted into the museum’s dinosaur gallery.

Participants will visit most of these rock formations during their short excavation vacation. They get their dinosaur fix in the Morrison Formation, while the Sundance Formation is overflowing with “souvenirs” in the form of fossilized squid shells.

“We’ll get to the Cloverly someday,” Frederickson said. “We could find raptors in that Cretaceous rock, but I don’t think anyone feels like walking three hours to get there today.”

Descending To Dinosaurs

After descending the “Grand Staircase,” a series of ledges dug into the hillside, the Family Dino Dig enters the Lower Sauropod Quarry.

This is where all the excavation and excitement have been focused for the last few years.

Rachel Gray, one of the preparators from CMI’s Paleo Prep Lab, gleefully did a quick tour of a massive hole in the sandstone layer covering the primary fossil site.

That’s where the museum’s exceptionally well-preserved Allosaurus, complete with belly ribs and extensive skin impressions, was found.

Each participant is carrying a bucket of essential tools: a paint brush, a dustpan, an X-Acto knife for fine details, and a “zog,” the sharp-pointed trowel that will do most of the work.

“They had ‘zog’ on them when we bought them, so that’s what we call them,” Gray said.

The Family Dino Dig was sequestered in an exposure of mudstone, around ten feet wide and three feet long. Peterson said they’d found the bottom halves of very long ribs in this spot last year and were intent on finding the top halves before the end of this session.

Another group of paleontologists was working in the Lower Sauropod Quarry that morning. They were from the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands, working on a significant discovery that was being kept under wraps — and wrapped in several layers of plaster, burlap, and tin foil — for the moment.

“What we can say is that it’s a big animal,” said Anne S. Schulp, a researcher with the Naturalis.

Peterson said the Lower Sauropod Quarry was likely a lakebed during the Late Jurassic. The dinosaur bones preserved in the mudstone layer at the site likely accumulated there after being carried by the current of one or more rivers that flowed into the lake.

“This was not a rainforest environment, by any stretch,” Frederickson said. “The rivers would dry up, which caused the lake to dry up. If the rain didn’t come fast enough, the animals that died would be washed together when the rains came back and would be buried together in the water, silt, and sand inside this redeveloping lake.”

What was immediately clear is that there’s no shortage of fossils in the quarry. Where there’s one, there will be others.

Slow Going Again And Again

Some of the many familiar faces at the Jurassic Mile are the Able Family. Aubrey and her son, Nico, 11, have been participating in the Family Dino Dig for three years, and her husband, Scott, and daughter, Thea, 9, have joined them for the last two.

The Ables live in Zionsville, a suburb of Indianapolis. Nico has vowed to become a paleontologist, so where better to take him for that first-hand on-the-job experience?

“We came here as soon as Nico turned eight,” Aubrey said. “That was the age limit. I couldn't have asked for a better vacation activity than this.”

Gray and Plata joked that Nico will be the first paleontologist with the 10 to 15 years of experience needed to get his first entry-level job.

Aubrey and the rest of her family have been having a blast too once she got over her initial paleo-paranoia.

“I was nervous,” she said. “I was thinking we were going to break history or mess something up. How can paleontologists handle kids and their job as paleontologists? But I was so impressed with how calm they were and how well they handle kids being kids.”

Nobody at the Jurassic Mile views kids and families as a hindrance to their work. In Frederickson's view, they’re an asset.

“We've learned that kids who are coming out here are the ones who take this very seriously,” he said. “They don't necessarily swing the knives around and whatnot. We have a pretty good eye on them to make sure they're not doing that, but they’re taking it very seriously.”

Even with heavy tools like hammers and chisels, the process of field paleontology is a slow and laborious one. That might seem like an impossible level of patience to expect from a child in the 21st Century of screens and social media, but Peterson has found the exact opposite to be true.

“They know every rock could potentially have a bone or tooth underneath it,” he said. “There could be a whole new species that we didn't know was here. There’s no fast way to do this. Slow is good, so I’m very happy with the pace these families are going at, because they’re taking it seriously.”

The Ables are one of many families that have repeatedly returned to the Jurassic Mile for the Family Dino Dig. It’s the allure of a once-in-a-lifetime experience stretched across multiple summers.

“They just can't get enough of digging for dinosaur bones, and we love to have them out here,” Trumpey said. “They come visit us at the museum, and we continue that relationship with them. Kids get experience with real science, hands-on, with actual authentic fossils, and you never know where that path is going to take them.”

‘Dr. Joe!’

The July sun got hotter as the day of digging progressed, but with a cool breeze and a shade structure overhead, nobody was discouraged by the heat or the sun.

With frequent water breaks, everyone was comfortable and eager to continue digging in the Lower Sauropod Quarry.

The Ables were poking at the edge of the exposed mudstone layer when they got a shiny reward for their labor — a small, serrated tooth from a carnivorous dinosaur, deposited near the cluster of ribs exposed nearby.

Gray was bouncing around, answering questions and telling jokes. Jorge Plata, another CMI fossil preparator, was already at work with a rock hammer and a bayonet, exposing a collection of oddly shaped fossils that turned into what Peterson described as “a catastrophe of confusion” by the end of the day.

“I’d love to tell you exactly what that is,” Frederickson told the assembled group, “but because of the way it’s positioned, we won’t know until we get it out.”

There were constant cries for “Dr. Joe” whenever a suspicious shape or color emerged from the gray mudstone. Laura Rooney, CMI’s curator of paleontology, was on hand with a tablet to photograph and document every find significant enough to be included in the museum’s collection.

That’s one of the prized achievements of the CMI Family Dino Dig. Kids might not be able to keep the six-foot rib or Allosaurus tooth they discovered, but their name will be forever associated with their discovery.

“What I love about this program is we don't put families in ‘the kids quarry,’” Frederickson said. “They're right beside us. They're digging the fossils that will go back to the museum and possibly end up on the dinosaur. We don't separate them from the science. They could be digging in the spot where the next great find or big skull will emerge.”

Nerding Out

At 3:30 p.m., all the tools were packed, the shade structures taken down, and the dinosaur bones were tucked in for the night, safely covered by a tarp held down by some of the plentiful rocks in the area.

It was a good day of dinosaur digging. By Peterson’s assessment, the day’s excavation revealed several rib heads, a backbone of some sort, and possibly the bladed half of an ischium, one of the hip bones, of a Diplodocus-like sauropod.

The other sauropod mounted in CMI’s Dinosphere was excavated from the Lower Sauropod Quarry. Frederickson knows they’re finding dozens of bones from multiple individuals, but suspects they might have lived and died together.

“We think these fossils all probably belong to the same individual amongst this larger herd that all died together,” he said. “What we know for sure is that we are and have been collecting multiple individuals of the same animal.”

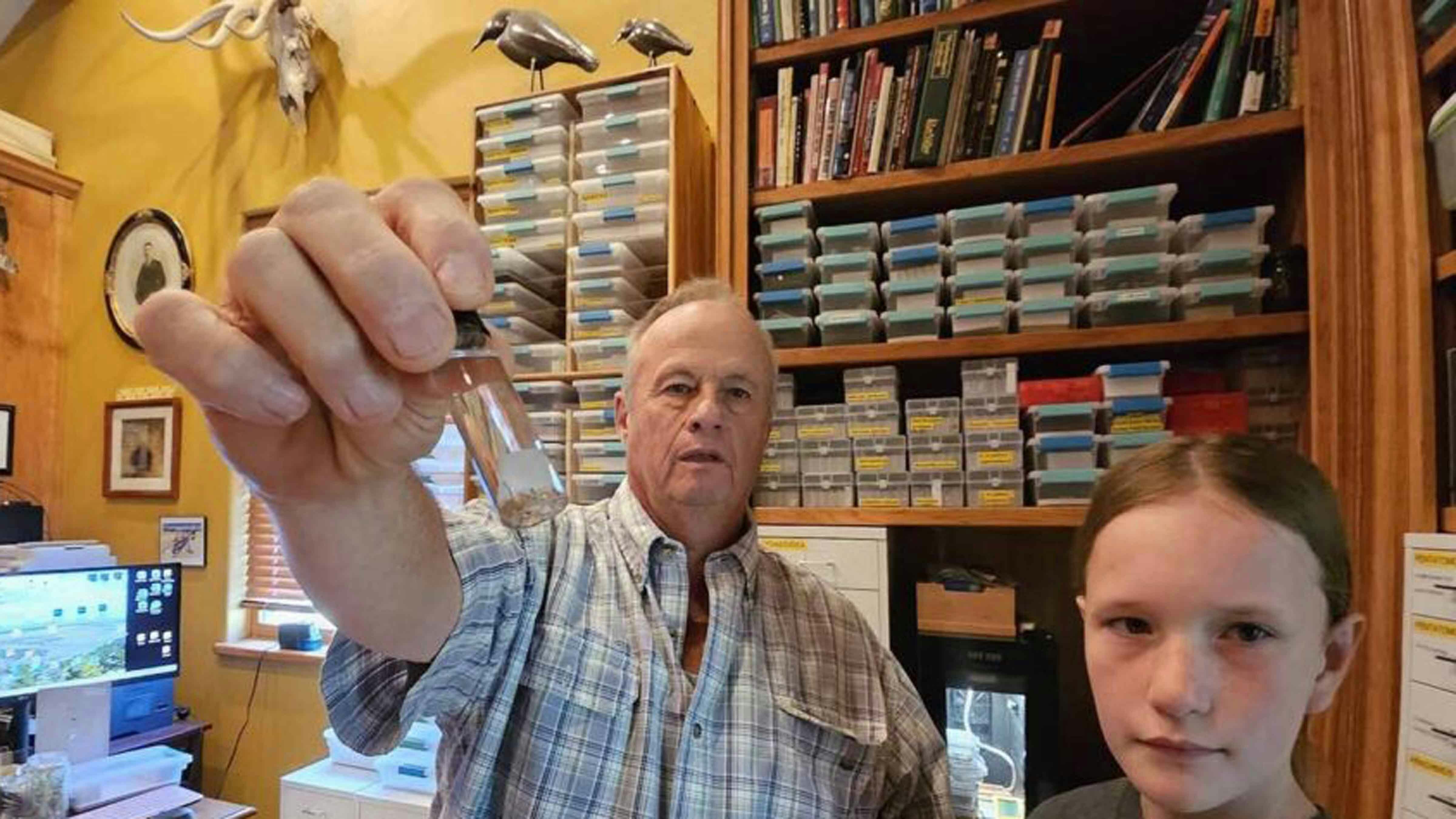

Big bones are great, but Peterson’s more excited about the much smaller fossils that have turned up at the Jurassic Mile. He wants to understand the diversity of animals that lived and died at the Jurassic Mile, and every scrap of fossil can add to their knowledge.

That’s where the sharp eyes and enthusiasm of Family Dino Dig participants come in quite handy. Frederickson has a treasure trove of tiny fossils found by kids that are exactly what he’s been looking for.

“This season, we found a really nice vertebra from a small lizard-like animal,” he said. “It could be an animal called the tuatara, Sphenodon, that is found in New Zealand. Last year, we found an inch-and-a-half-long jaw in the same area.

“I find those fascinating, because they're telling us about the ecosystem and as a whole, not just the giant animals, but the little things running around their feet.”

Aubrey didn’t get her name in the book that day, but the thrill of discovery is still intoxicating after three summers at the Jurassic Mile. She’s thrilled that Nico’s gaining so much experience and knowledge, but admits that’s not the only reason they keep coming back.

“I probably nerd out more than the kids do, honestly,” she said. “I try to talk to people in science or who are really into their field, and they're really zoned in. They won't stop whatever they're doing to talk to a kid, or talk to the big kids like me, answer questions, or help us out.

“Everyone here’s so knowledgeable. They’re not only teaching and talking to us but also give us so much freedom while showing us how to do this responsibly.”

Good For The Goose And Gander

Planning any family vacation is a daunting endeavor, let alone one tailored to a passionate paleo enthusiast. Fortunately, one of the perks of the Family Dino Dig is that once you get to Wyoming, everything’s taken care of.

CMI’s staff and program participants stay at hotels in Cowley and Lovell during their weeklong excavation vacation. Everyone enjoyed fresh box lunches prepared by the Mustang Café & BBQ in Lovell, which had served breakfast to everyone that morning and every morning during their stay.

Trumpey said everyone’s benefited from the network of “small town support” they gained over the years. Compared to most other paleontology expeditions that involve camping in remote areas, hours away from the nearest signs of civilization, the CMI Family Dino Dig is downright luxurious.

“It’s nice to have a short drive out to the site,” she said. “It’s great to have that kind of support in Lovell and Cowley.”

For the Ables, the Family Dino Dig has opened their eyes to the wonders of Wyoming. Dinosaur digging might be the highlight of their trips, but they’ve learned to linger and see more of what the Cowboy State has to offer.

“We’re planning to come back every year and do more around Wyoming,” Aubrey said. “Honestly, when I tell people at home to go to Wyoming, they're like, ‘Why?’ So, I tell them that the Family Dig this is what we're going for, but there's tons to do out here, and our kids talk about Wyoming in school all the time.”

There’s excitement and the potential of discovery along every inch of the Jurassic Mile. And as long as CMI’s paleontologists and their partners are there, kids and families will be right beside them, making the next big dinosaur discovery.

“Everybody sees something differently,” Frederickson said. “The person looking for tiny fossils might miss the giant bone right next to them. Having as many diverse eyes as possible makes sure we don’t miss anything.

“For so many people, digging for dinosaurs with a real paleontologist for a couple of days is a lifetime goal, and we’re here to make it the best experience possible.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.