A random thought after watching a documentary took root, then faith and effort motivated him to put one foot after another for 1,500 miles across Mongolia.

That Jackson Pastor Brian Hunter, describes his 2013 mission to run across the East Asian country, where he got up close and personal with the abandoned street orphans across the nation sandwiched between Russia to the north and China to the South.

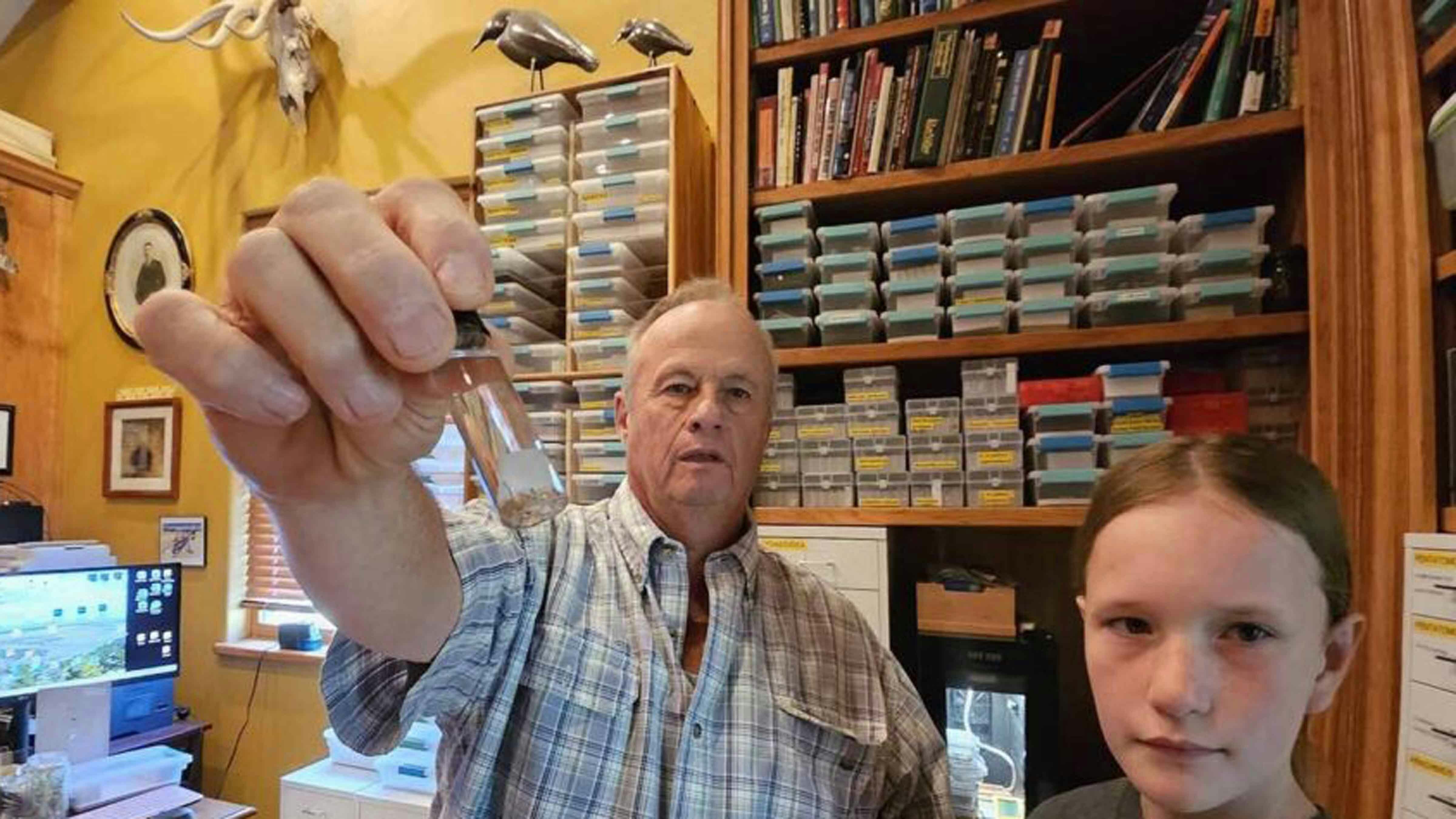

Hunter’s Wyoming church is called the Tribe.

Now the legacy of his 1,500-mile trek across Mongolia 11 years ago is taking a new twist. A film crew’s documentary footage of his run, locked for seven years in legal limbo, has become available to him.

Now his new thought centers around the possibility of using the video to benefit the same orphanage and street kids who struggle to see any future in Mongolia’s Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital city in the world.

“Our hope is to make a documentary film, released episodically that chronicles the adventure and highlights the plight of these children,” he said. “And goes back to see some of the ‘rest of the story’ tales of what our run accomplished.”

Any proceeds of the film would be turned over to the orphanage and ministry he initially connected with in 2013.

Hunter, 50, said his story begins when as a self-described “climbing dirtbag” and “ski bum” in Colorado he met his then girlfriend, moved to Jackson in 1998, got married in 1999 and then became involved in a local church. He felt the call to ministry, and, at 35, headed to Oral Roberts University in 2007 for ministerial training.

Following graduation, he and his family remained in Tulsa and ministered at a church. In 2011 he saw a documentary about two guys who motorcycled across the world, but when they entered Mongolia, which Hunter describes as “stunning and beautiful,” the riders experienced hardship.

The Thought

The Mongolia segment seemed to capture his heart, and he had the thought of doing a trail run in the country followed by the thought of just running across the entire nation. Hunter said he does not consider himself a runner, but had done a 50K race a couple of years earlier.

“I immediately dismissed that thought as like early onset of midlife crisis or something,” he said. “But the thought kept bubbling back up and over the course of the next two years I couldn’t shake or escape the thought of running across the country Mongolia.”

Hunter said he and wife, Lissa, prayed about those thoughts and came to the point where they put “yes on the table.”

Nearly immediately after that, he learned about the plight of the orphans in Mongolia’s capital who have been abandoned and forgotten by society since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The abandoned children live at the city’s dump and to stay warm go down in its sewers to survive.

Hunter said many are trafficked in the world’s sex trade.

“I’m not going to run across the country just to sightsee, I’ve got better things to do with my knees and my time,” he said. “And so, I said, I know what I will do, I’ll run to raise money for orphaned and vulnerable children living in the capital city.”

Research brought him in contact with a church, and those connections through its pastor led to a person in the congregation who runs a tour operation who would be key to setting up the run and providing support services. Hunter also met through the pastor a Mongolian named Baska who had been raised in the slums and had dedicated his life to helping the street kids and orphans. He also connected with an orphanage that focuses on rescuing street kids and seeing them adopted by Mongolians.

All the logistics and funds fell into place for journey, for which Hunter credits God. He believes God showed up in many ways as they prepared and showed both him and his family how to do the trip. His family, Lissa, with daughter, 10, and son, Kai, 8, at the time became his support crew along with two drivers, the tour guide who provided interpretation services and the four-wheel drive vehicles and equipment for the trek.

The film crew joined the expedition at the last minute.

The Run

Hunter said only 2% of the nation’s roads are paved, he ran across the country from the Russian border in the west to the Chinese border in the east. The trek covered five mountain ranges and two deserts and several tiny communities that he characterizes as half the size of Wyoming’s smallest town. Typically, the community would have a store and maybe a place for fuel. They were about 10 days apart accounting for Hunter running a mile every 12 minutes or so.

“My heart focused on the finish line and the good that we were accomplishing and my head focused on the next step in front of me,” he said. “I never got the Chariots of Fire moment, I never got the runner’s high, I never felt this is amazing, I can just keep going and going. The last 10 miles were every bit as hard as the first 10 miles.”

Dangers included getting lost from his support team, the big angry dogs that Mongolians used to keep wolves away from their sheep, and drunken Mongolian men who liked to find him alone on the trail and harass him — asking for his shoes, sunglasses, or something else.

He said statistics at the time showed about 80% of the nation struggled with alcoholism due to the availability of cheap Russian vodka.

A typical day would see him up early for breakfast out of the tent, then he would run ahead while his wife, kids and rest of the team broke camp. When they caught up with him down the road, he would stop for a snack. The team drove ahead to set up for lunch. When he would arrive, he would eat, try and take a 20-minute nap wrapped in a blanket, and then take off down the road.

The running generally lasted 12 hours a day, six days a week, and then just as in the Bible, rest for everyone on the seventh day. The only perk across the fenceless terrain was the stop in the small community where a warm Coke, a Russian-made chocolate bar and chips might be the treat.

He believes the hand of God was on he and his family during the whole experience.

“We were in country for two-and-a-half months,” Hunter said. “The entire time my children never got injured, never got sick, my wife never injured. One day 10, I got a blister because I wore a new pair of shoes that I hadn’t broken in.”

The Finish

The finish line was inside the secure “no-man’s land” area at a fence on Chinese border that his “fixer,” the Mongolian tour guide, was able to negotiate with both the Mongolian government and the Chinese.

On the other side of the border, he could see a city with high-rise buildings lit up that could contain up to 20,000 persons but had hardly any “because nobody wants to live in the middle of nowhere.”

After touching the gate to China and posing for photos with smiling Chinese guards, it was mission accomplished. The support vehicles could not follow them into the zone, so they walked back.

“The first thing I did was take my running shoes off, I think I left that pair right there in the grass, and put my flip-flops on,” he said. The trek used up six pairs of running shoes.

For the fundraiser, he set up a non- profit called “Strong to the Finish” and raised $50,000 through the run. With those funds, property was able to be purchased for the man Baska’s efforts to build a refuge center near the city dump for street children. Funds also went to the orphanage.

Relationships with the orphanage, Baska, and the church in Ulaanbaatar continues. Hunter led a mission’s trip from his church in Jackson to Mongolia a few years ago. And the pastor of the church in Ulaanbaatar has visited his congregation.

The experience of tackling a run across the nation changed Hunter and bonded his family in a special way, he said. Hunter said he had the easy part in running every day while his wife and kids had to break camp, set up camp, deal more with the relationships inside the crew and do without the western comforts that Americans take for granted.

“I’ve never served in the military, but in a similar way that guys from the same military unit are bonded through opposition and hardship and suffering … I have that with my family because of the experience that we went through,” he said. “Mongolia dug a deep well of physical and mental fortitude in my soul that I continue to draw on every day.”

After arriving back in the states, the family returned to Oklahoma, but in 2014 they had the opportunity to return to Jackson. In 2016, he started his current church ministry.

The Footage

Hunter said shortly after returning from Mongolia, he learned that the film crew’s production company “went insolvent.” There would be no documentary of the trip and the struggles of the orphans in the Mongolia’s capital. Video captured by the crew was tied up in litigation for seven years until earlier this year when Hunter was able to acquire it.

“We have all of the raw footage, and we are looking for funding to finish production of this episodic release,” he said. “If people are interested in helping to fund or produce this documentary, the funds from this production will go toward these organizations in Mongolia. I’m not looking to make a dime off this.”

People interested in learning more about that project or make donation can do that through the non-profit Strong to the Finish. While the nonprofit’s website is currently being redesigned, Hunter can be contacted at brian@strongtothefinish.com or through the church’s website, tribejh.com.

Hunter also has written a book about his trek across Mongolia and the lessons gleaned from it titled “Strong to the Finish.”

His big adventures may not all be behind him. Hunter said he as a couple “dreams” he is still pondering and praying about. No running is involved.

“It is a dream to ride my bike from Egypt to Israel retracing the route of the biblical exodus,” he said. “Another dream is that I would like to ride my bike around Tibet and see the high arid desert of Tibet.”

Contact Dale Killingbeck at dale@cowboystatedaily.com

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.