The Red Gulch Dinosaur Trackway is a unique record of a time when Greybull, Wyoming, was beachfront property and when dinosaurs roamed the shores of an ancient sea during the Jurassic Period.

More than 160 million years later, all that's left are the ghostly footprints of dinosaurs that paleontologists will probably never find.

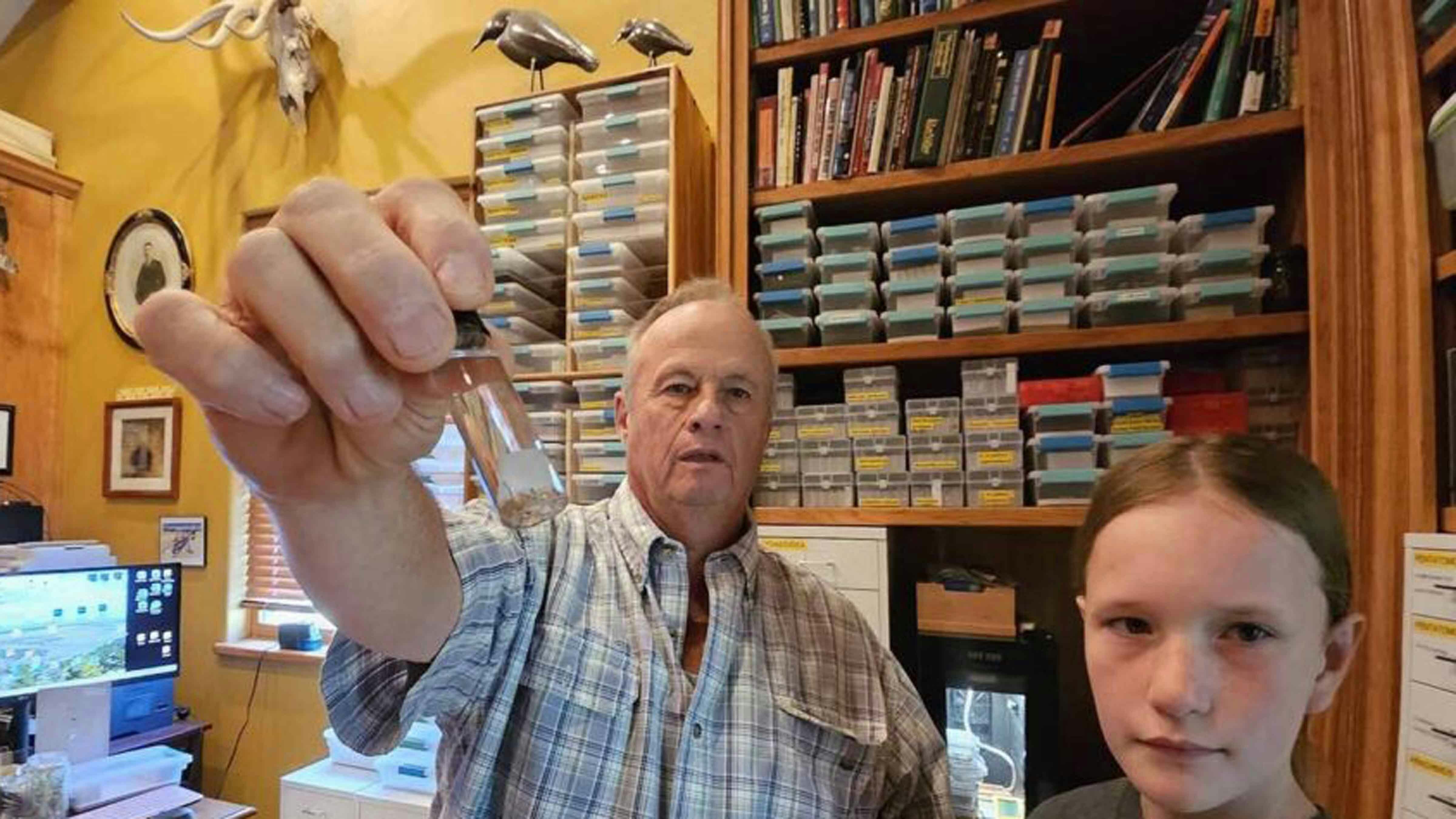

That was the prehistoric scene Dr. Erik Kvale brought to life during a June 15 Wyoming Walk, a program created by the University of Wyoming and Wyoming State Parks. More than a dozen people came to hear the story of the dinosaur trackway, which Kvale helped discover in 1997.

"This surface has over 800 dinosaur tracks that have been mapped," he said. "It's become a very important site from a time when we know dinosaurs were alive, but we can't and may never find their bones."

Finding The Beach

Kvale is the executive director of the Big Horn Basin Dinosaur and Geoscience Center in Greybull. He grew up in Greybull and decided to retire there after a decades-long career as a geologist with several agencies.

Today, Kvale is leading an effort to fill a new museum in Greybull with replicas of extraordinarily complete dinosaur skeletons found near Greybull and Shell.

In 1997, Kvale was trying to create an outdoor geology experience for K-12 students through a grant from the National Science Foundation in and around the Greybull area. He was hiking through BLM land with his aunt and uncle, Row and Cliff Manuel, and was looking for interesting rock exposures to include in the workshops.

"We were looking at ripples in the gully that had formed from a recent rain," he said, "and we thought it'd be nice to have modern ripples and then show ancient ones in the rock record to show the processes were the same. I'd been by this road several times and remembered this very nicely rippled surface. We thought what a great analog we've got, so we decided to swing by here."

It was 10 a.m. when Kvale and the Manuels reached a large slab of rippled limestone that had been freshly exposed by water flowing from a culvert installed under the road. In addition to the rippled surface they were looking for, they found marine fossils scattered in the rock and around the area.

Cliff Manuel believed that they might find dinosaur tracks in the area. Kvale disagreed.

"Cliff said, 'Do you think we'll see dinosaur tracks,' and I said, ‘No, it was the wrong formation,’" Kvale said. "And no sooner had I got those words out of my mouth when I'm looking right at a dinosaur track. And I said, ‘Except for this one.’"

The three-toed track was only a few inches long and only slightly larger across, but it was undeniably from a dinosaur.

The first dinosaur track led to several more from the same animal, intersected by the different-sized tracks from other dinosaurs moving across the same rippled rock.

"We were off like rockets at that point," Kvale said.

Making Waves

After a morning of following dinosaur tracks, Kvale and the Manuels contacted the Wyoming Bureau of Land Management to alert them of the discovery of a dinosaur footprint site. The BLM immediately picked up the trail and started working to establish the discovery as an interpretive site.

Kvale headed a research team with scientists from Kansas State University, Dartmouth College, Indiana University and Purdue University Fort Wayne. The team worked with the BLM and the Universirty of Wyoming to do a thorough paleontological and geological study of the tracksite and the surrounding area.

"Brent Breithaupt ran the U.W. Geological Museum at that time, and he put together a group of people to describe and map the tracks," he said. "My team was responsible for doing the overall geology of the area, figuring out what kind of environment these animals had walked around on."

Their work discovered hundreds of dinosaur tracks in the rippled limestone. They dated back to the Middle Jurassic Period, 160-180 million years ago, making it one of the only sites of its kind in North America.

“This surface is the only evidence that dinosaurs existed in this part of Wyoming in the Middle Jurassic,” Kvale said.

Following Footsteps In The Ballroom

Kvale led the tour down the boardwalk and onto the rippled rock, which is informally known as "the ballroom." Finding one tridactyl (three-toed) footprint, let alone hundreds of others, was difficult in the mid-morning light from an overcast sky.

Using his trained eyes, Kvale placed a poker chip at the end of the middle and longest toe of one of the largest dinosaur tracks in the rock. The group followed as he put another chip at the end of the same toe of the next track in the sequence, followed by several more, each an equal distance apart.

Chip by chip, he was revealing the long strides of an ostrich-sized dinosaur preserved in the rippled limestone until it disappeared under a large mound of sediment at the edge of the exposure

"These dinosaurs were toe walkers," he said. "You don't see a strong heel in any of these tracks. There's only one kind of animal that could have made a print like that at this time, and that would have been dinosaurs."

In the Middle Jurassic, the rippled limestone exposure was a sandy beach at the edge of a warm, shallow inland sea. It was deposited in the Sundance Formation, a thin layer of rock widespread across Wyoming full of fossils of squid, clams and marine reptiles but entirely devoid of dinosaurs.

"The Sundance Formation is known for its marine fossils," he said. "You've probably seen the little bullet-shaped fossils from ancient squid, called belemnites. There's also Gryphaea, which are called 'devil's toenails.' Those are fossils of oysters."

The Sundance Formation also contains fossils of marine reptiles, like plesiosaurs. But since it was an aquatic environment, and dinosaurs lived on land, paleontologists hadn't and didn't expect to find any dinosaur fossils.

"This surface is the only evidence that dinosaurs existed in this part of Wyoming during the Middle Jurassic," Kvale said.

Old And New Again

As people found and followed the dinosaur footprints, Kvale explained the paleoenvironment of the Red Gulch Dinosaur Tracksite, resurrected through the research team's work. The composition of the rippled limestone rock revealed what the area would've been like during the Middle Jurassic.

"This limestone is made up of little, tiny spheres called oolites," he said. "You only get oolites from an ocean, where it's being agitated back and forth. South Florida and the Florida Keys have oolites, so that's our analog.

Further research of the site has revealed signs of "ABS," geological shorthand for "amorphous blobs." The team determined that depressions at the edge of the tracksite had been left by algal mats accumulating on the prehistoric beach as the tide went out.

Kvale's team knew they could find a modern-day ABS analog in the South Persian Gulf in the Middle East. Since they didn't have the funds to make a trip and observe it firsthand, they searched for and found another analogy in South Florida, where the beaches were covered with green algae at low tide.

There were also several U-shaped holes in the rock, sometimes cutting into the dinosaur tracks beneath. Those were the bottoms of burrows, dug out by shrimp that lived in the sediment that covered the tracksite when it was submerged under seawater.

"We are literally in very last stages before a rising sea level completely inundated this area, and that sea level must have come up very rapidly after these tracks," he said. "Within a few months to years perhaps, but we don't know."

The site's paleoecology makes it even more extraordinary that it exists at all. The beach where the dinosaurs roamed was exposed only briefly, yet it was a well-traveled thoroughfare at that moment.

Dinosaur Doings

Dinosaur footprints are trace fossils, any fossils that preserve something left behind by an organism, whether that be tracks, bite marks, or droppings. Since body fossils, like bones and teeth, usually aren't preserved alongside tracks, it's nearly impossible to determine what kinds of dinosaurs left which tracks.

The tridactyl tracks at Red Gulch were most likely left behind by bipedal dinosaurs, ranging from a few feet long to the size of a large emu or ostrich. Most paleontologists believe the tracks belonged to theropods, carnivorous ancestors of Tyrannosaurus rex and Allosaurus, but there's no way of knowing with certainty.

"The ballroom" is cluttered with several different trackways from different-sized dinosaurs. However, many seem to be heading in the same direction, which Kvale and his team interpreted as the dinosaurs heading from shallow water into deeper water.

"If you watch a dog or a human walk, we don't walk in straight lines," he said. "We think we do, but it's actually slightly curvy. If you look at these tracks, these dinosaurs are doing exactly the same thing. There aren't any perfectly straight lines here."

Unfortunately, not much else can be said about the dinosaurs and what they were doing on the edge of the Sundance Sea. Kvale speculated that they might have been "beachcombers," eating marine organisms in the shallow water or carrion that washed onto the shore but acknowledged that was "entering the world of conjecture."

"'We're sure we're on a beach, and the dinosaurs were walking in this area towards deeper water offshore, but we can't say anything else with certainty," he said.

Ghosts of Greybull

The Red Gulch Dinosaur Tracksite is a few miles off U.S. Highway 14E, east of Greybull. A dirt road leads to a gravel parking lot and a boardwalk that guides visitors to "the ballroom," where the dinosaur tracks are located.

Kvale said more tracksites from the Sundance Formation have been found on BLM and private land close to Red Gulch. The original site is just one exposure over an immense area thoroughly tramped by the feet of dinosaurs.

"This is a small section of one of the most extensive mega track sites in the world," he said. "There's a three-square-mile area right here that has dinosaur tracks. If you use the same track density, the number of tracks per square meter that we see at Red Gulch, this area conservatively has a million dinosaur tracks in place."

There's even one exposure of dinosaur tracks in the Gypsum Springs Formation, a layer of rock roughly four million years older than the Sundance Formation. Fossils of any kind are scarce in the Gypsum Springs, yet an exposure of dinosaur tracks is preserved in the one-of-a-kind site that Kvale called "the Yellow Brick Road."

While there are potentially millions of dinosaur tracks in and around Red Gulch, there's only been one dinosaur bone from the same period. Kvale said the only dinosaur body fossil from the Sundance Formation is a single scrap of unidentifiable bone in the vast collections of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.

"There are always possibilities that we could find some dinosaurs in the Sundance Formation," he said, "but no skeletons have ever been found in this formation, and the rocks that would've preserved them have been eroded away in the millions of years since."

That's why the Red Gulch Dinosaur Tracksite and the other tracksites near Greybull are so revered in the paleontological world. The hundreds of footprints preserved there are currently the only evidence of these 180-million-year-old dinosaurs that paleontologists may ever find, here or anywhere.

By the time the Wyoming Walk of the site ended, nearly everyone had attempted to follow a dinosaur, footstep by footstep, across the rippled limestone rock. They were on that prehistoric beach for a brief moment, following the ghostly trails of long-dead dinosaurs.

"More than likely, these animals were surviving by whatever was along the coastline," Kvale said. "We've got 800 of them here, maybe a million or more in the immediate area, and all those tracks are heading towards the ocean. The ocean and the dinosaurs are gone, but the tracks are still here."

Contact Andrew Rossi at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.