More than 100 years ago, torrential rains swept through much of Wyoming in July and September 1923, but it was at near-Biblical proportions in the central part of the Cowboy State, flooding out towns and farms and killing at least 33 people.

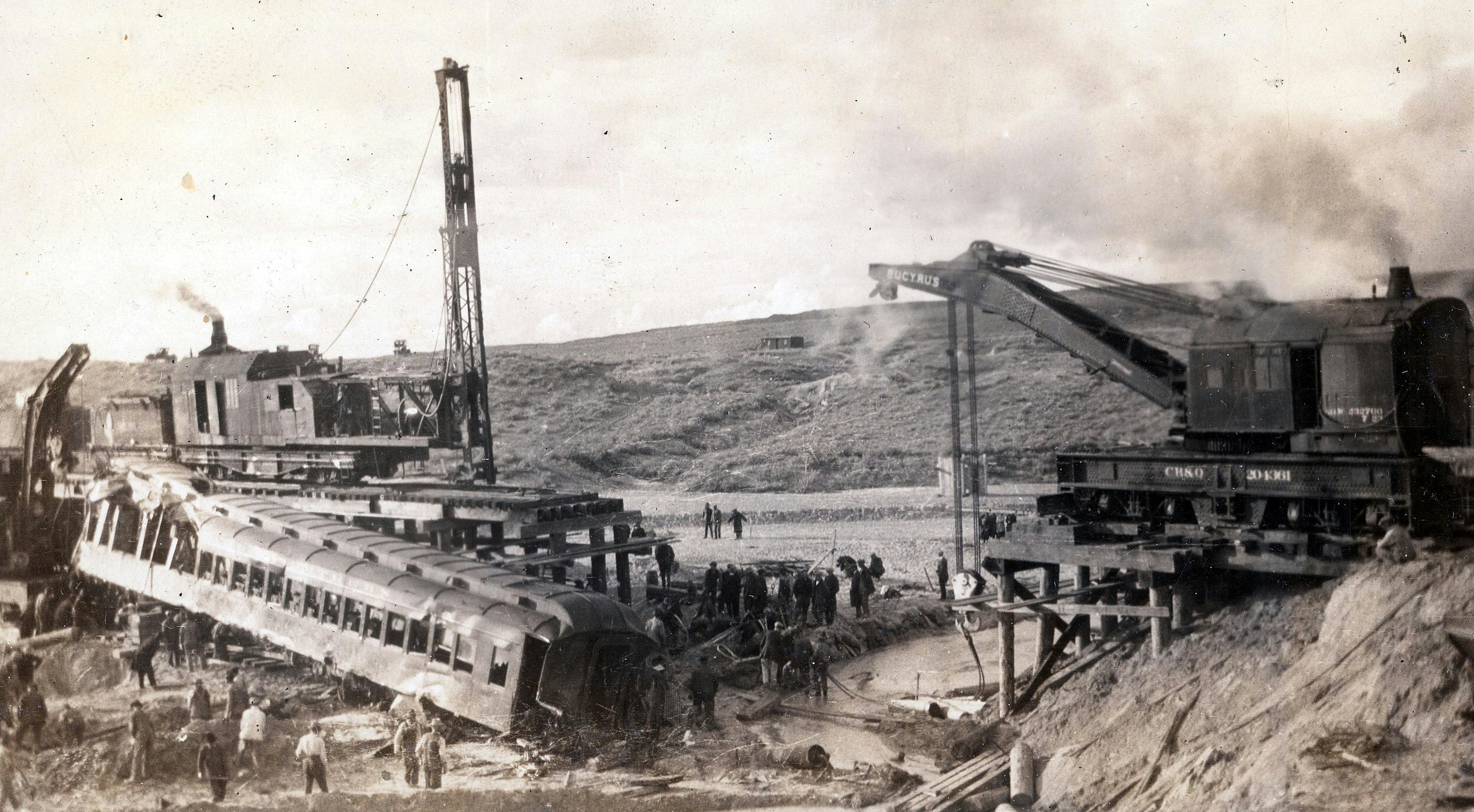

The rains in September came down for five days and caused the Cole Creek train disaster near Glenrock, the worst train crash in Wyoming history when a bridge was taken out by flood waters, killing 18. But they also inundated the Powder River and Bighorn River basins.

Just a couple months before in July was what the federal government characterized as a 60- to 100-year flood in central Wyoming that put much of Thermopolis under water, sent rail cars down the creek at Bonneville, and washed away steel railroad bridges spanning rivers.

A ranch family in Lysite spent 36 hours clinging to a tree, two men lost their lives near Shoshoni, and residents in several towns lost homes or dealt with flood damage to their buildings.

‘Greatest Flood On Bighorn River’

A U.S. Geological Survey report published in 1925 gave an account of the amounts of water rushing through the region’s rivers and streams as well as the amount of precipitation that fell on the Bighorn River Basin.

“From July 22 to 26, (1923), a series of heavy rains in the Bighorn River Basin caused the greatest flood on the Bighorn at Thermopolis in the last 24 years for which records are available,” the agency wrote.

Bonneville was at the center of the biggest rainfall and storm event, which stretched about 90 miles east to west and 65 miles north to south. Thermopolis was at the northern edge, and the southern edge did not quite reach the Sweetwater River. On the west was the Diversion Dam on the Wind River and the east the little town of Arminto on Alkali Creek.

In Bonneville, a railroad agent for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad reported a severe thunderstorm with lighting began at 10:30 p.m. on July 23, 1923, and continued until about 3:30 a.m. July 24. He estimated the rainfall at several inches.

That cloudburst over Muddy Creek on the Wind River Indian Reservation 16 miles to the west of Bonneville caused Muddy Creek to sweep away a ranch cabin and sheep wagon, claiming the lives of ranch owner Cleve Whittaker and his herder, Floyd Jennings.

“Whittaker was swept away by a wall of water at midnight on Monday as he stepped from his ranch house door. Jennings who was hurriedly clothing himself in the sheep wagon close to the ranch, was also drowned when the flood waters swept the wagon down the raging waters of the creek,” The Casper Daily Tribune reported on Thursday, July 26, 1923.

In Riverton, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Manager H.D. Comstock reported heavy rain on July 22, 1923, for three hours, and then sustained heavy rain at 10 p.m. July 23 though 3 a.m. July 24. At 5 p.m. July 24, he estimated a rain event over an area about 10 miles in diameter that dumped 2.20 inches of rain in less than an hour.

As those raindrops slid down rocks onto the ground in rivulets, reaching creeks and then the rivers, bad things began to happen.

Badwater Creek in Bonneville hit flood stage at 9:45 a.m. July 24, and the Bighorn River at Boysen Dam north of Shoshoni at 5 p.m. The Wind River hit flood crest in Riverton at 4 a.m. July 25.

July Disaster

The result for most in the zone was disaster.

“Thermopolis Is Inundated” screamed a banner headline on the Casper Daily Tribune on Wednesday, July 25, 1923. “Flood Havoc Is Piling Up. Part of Hot Springs Center Buried by Overflow from Bighorn; Damage to Railroads Will Be Enormous,” continued the sensational subheadlines.

At Boysen Dam, the power plant stopped generating after taking on 2 feet of water in its powerhouse. The water was 20 feet over the dam and nearly 5 feet deep in a railroad tunnel. In Thermopolis, a portion of the town’s homes near the railroad were inundated with flood water and people slept in the depot.

The Badwater Creek became a monster in Bonneville and the surrounding area. The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad had 20 miles of track washed away, three steel bridges destroyed and the Bonneville community was covered with 2-5 feet of water.

“The Badwater, at its highest point in the memory of the oldest inhabitant, washed out the main line of the railroad and all the east end of the yards,” the Casper Daily Tribune reported July 25, 1923. “Two boxcars loaded, one empty and two cabooses were swept into the river and two small residences disappeared in the swollen waters of the stream.”

All telegraph and communication lines to the flooded areas were knocked out for a time. The Casper Daily Tribune reported that locals resorted to more crude techniques to get messages back and forth.

“Bonneville and Shoshoni, three miles apart, established communication this morning by tying notes to stones and hurling them across the boiling waters of (Badwater) Creek,” the newspaper reported.

Rescue Needed

To the east on Badwater Creek at Lysite, a railroad section crew and a ranch family were found holding onto a tree for their lives.

“Perched in the branches of a tree standing in 25 feet of water, the section crew from Lysite with a rancher, his wife and two children, aged five and seven years, were rescued after 36 hours at 5 p.m. on Tuesday,” the Casper Daily Tribune reported. “They had climbed to safety just in time to save their lives and were exhausted from no food, lack of sleep and exposure when they were taken down by an inspection party from the C.B. & Q.”

The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy took a big hit from its loss of 20 miles of track. Traffic was stopped and then rerouted until track could be replaced. The Chicago and Northwestern Railroad lost five bridges as well as 500 feet of track between Shoshoni and Hudson, Wyoming, were washed out.

The late July rains would not be the end.

Fall Rains

From Sept. 27-29, 1923, rains again hit central and northern Wyoming.

At Glenrock, the rainfall washed out the bridge over Cole Creek on Sept. 27, sending the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy train into the swollen stream bed and killing 31 people. It was the worst train disaster in Wyoming history.

The north central region of the state along the Bighorn and Powder rivers would see major property losses. Parts of Thermopolis were again underwater, but not as severe as a couple months earlier.

“People living in the lowlands of Basin and Greybull were forced to move,” the U.S. Geological Survey reported. “Many of the streets of Greybull were covered with water to a depth of three feet.”

“No one slept in Greybull on Saturday night (Sept. 29, 1923),” the Casper Daily Tribune reported Oct. 1, 1923. “Every inhabitant who could be active was busy in an effort to save either his own fortunes or the fortune of a friend. The residents worked all night.”

In Buffalo, the Buffalo Bulletin reported a rancher named Dave Muir estimated damage along the Powder River as “incalculable.” Another rancher lost 4,500 head of sheep.

In Arvada, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad’s 270-foot steel bridge that sat on concrete piers was taken out. Residents in the valley lost their hay, their homes and much livestock.

In Salt Creek, the gas plant was under 6-7 feet of water.

“The bridges on both the north and south end of the oil camp were washed out,” the Buffalo Bulletin reported Oct. 4, 1923.

40-Year Flood

Sheridan residents experienced flooded basements and streets.

“The general rains that caused the September flood on the Bighorn River covered the entire drainage basin of the Power River and extended north into Montana,” The U.S. Geologic Survey reported. “The flood on the Powder River was the largest that has occurred in the 40 years that white settlers have lived in the valley.”

In the following months, railroads would spend millions of dollars replacing track, filling washouts and repairing or replacing bridges. The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy would replace 100 miles of track, the Chicago and Northwestern and the Union Pacific had track to replace as well.

The Casper Daily Tribune reported Feb. 3, 1924, that Chicago, Burlington & Quincy needed to replace the line from Lysite to Bonneville and would spend a total $1.36 million on the Casper division of the railroad. That would be $24.8 million today.

After fixing the major washout following the July rains, the railroad again had to deal with the Badwater Creek taking out repaired track and fills in the September deluge.

“Years ago, the Indians named the creek that has its headwaters east of Lost Cabin and flows into the Bighorn near Bonneville the ‘Badwater.’ For the last 40 years settlers and visitors of that part of the state have been attempting to figure out the origin of the name,” the Casper Daily Tribune reported July 25, 1923. “The recent flood stage to Badwater settled for all time in the minds of those who were present the reason for the name.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.