Stories of Wyoming and the West are things that a University of Georgia professor and expert on pecans treasures alongside a few dozen small carved figures handed down to him that preserve the Code of the West.

Those carvings were the handiwork of a young rancher who did a pretty good job whittling away his time watching sheep somewhere around Casper prior to World War II.

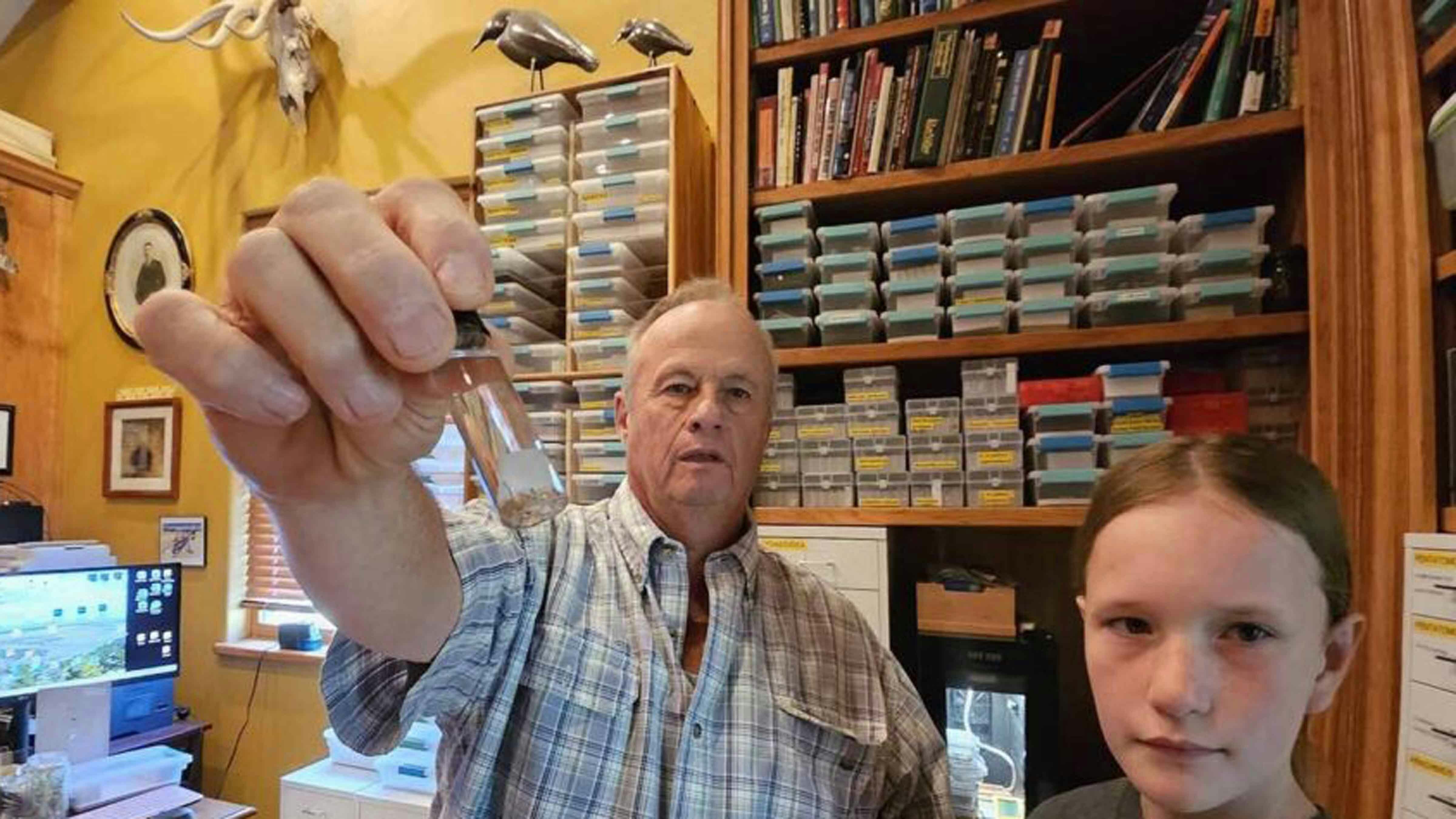

The artistry of former Casper cowboy and rancher William “Bill” Evans still is displayed in rudimentary dioramas he made that are kept by step-great-grandson Lenny Wells.

“Even though he was living in Georgia, I think his heart always remained in Wyoming,” Wells said. “He always talked about it and surrounded himself with things from that time in his life.”

But the wooden cowboys, horses, cattle and more depicted in Evans’ artwork weave a greater story about a man who grew up around Casper on ranches and served in the military in World War II.

Evans fell in love through a pen-pal relationship, moved to Georgia, but kept his Wyoming memories alive through his art as well as a revered sheep wagon.

Evans was born March 5, 1907, to Horace and Maude Evans, who were among the many families experiencing the boom-bust cycles of the Casper region in the early part of the past century. Horace Evans came to Wyoming on a cattle drive from Kansas and never left.

His life’s journey would take him all over the world — to the Pacific in World War II, the Pacific northwest and finding his lifelong love in Georgia. But through it all, he kept his hands busy whittling.

At the time, he likely didn’t consider it art. They’re rudimentary figures that somehow are infused with deep Western culture and Wyoming’s famous Code of the West.

There are tiny cowboys, horses, a rendering of his beloved sheep wagon — all doing everyday cowboy things, like sitting cross-legged eating a plate of chow, trying to put a rope on a horse and even a Chinese trail cook brandishing a huge knife.

He’d build his own, small Western world by arranging his carvings in their own cowboy camps. Decades later, the result of a man whose heart was always in Wyoming is a collection of spectacularly unique cowboy art.

Memories Of Casper

In a memoir of his life, Bill Evans recorded stories he heard as a boy about his father working as a Teamster, Evans’ first day at Central School in Casper and going to King’s Mercantile store on West Second Street for candy. He wrote about his grandmother living in Mills.

His father built and operated a tourist camp and store in Hell’s Half Acre.

Bill Evans worked at Standard Oil until he was laid off during the Depression and then wrote about going to Hell’s Half Acre 45 miles west of Casper in the fall to hunt rabbits with family as a means of earning money.

“We shipped them to Denver where we sold them for $1.50 a dozen. I killed from 40 to 80 a day, and got about the same,” he wrote. “We had to shoot them with .22 rifles and shoot them in the head or they weren’t worth shipping. The rabbits were plentiful, but we had to cover a huge area, we used a pickup truck and a tent part of the time.”

In 1931, he filed on a homestead and worked it with is two brothers for the next 10 years.

“My two brothers, Wilson and Bob, and I operated a small ranch until 1941,” he said. “We sold that place then and leased a ranch at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. World War II broke out then and put our ranch operation out of business, and I’ve not lived in Wyoming since that time.”

Wells said that it was while ranching and out on the sheep wagon in possibly his late teens and early 20s that Bill Evans picked up wood and knife and started carving out a timeless legacy of little figures that captured the culture he loved.

In addition to cowboys, horses and cows, his scenes of characters depict a roundup and chuck wagon meal.

“He painted them and came up with the scenes and dioramas for it,” Wells said. “He was a carpenter by trade, and he ended up back here in Georgia at the Marine base as a carpenter.”

World War II

When his ranch life was interrupted by World War II, Bill Evans joined the U.S. Navy and ended up assigned to a gun crew on the USS Enterprise after the battle of Guadalcanal.

“On one of his first cruises out of port, they were in a battle, and he saw the USS Hornet get bombed and sunk,” Wells said.

Evans’ war experiences included being involved with action around New Guinea, the Philippines, Gilbert Islands, Marshall Islands, Guam and Saipan.

“After the war he went to visit his mother, who had remarried and moved to Clarkston, Washington,” Wells said. “Then he visited his siblings back in Casper and hauled the sheep wagon back to Clarkston, where he got a job as a carpenter.”

Evans' father Horace died in 1941.

In his memoir, Evans describes carpentry as “the only thing I knew anything about, except cows and sheep.”

While working in Washington, he had a friend who started a Christian pen-pal ministry that provided names for people who wanted to correspond with each other.

His mother worked for the organization and one day Evans helped her sort the mail. A letter caught his eye.

“It was from a Pauline Reed at Cordele, Georgia,” Evans wrote in his memoir. “She enclosed a small photo of herself. Well, I put the photo and letter in my pocket and answered it myself.”

After corresponding for a few months, he drove to Georgia to meet her, love took hold, he courted her, and the couple was married in 1946.

The man from the West was moving South. But he needed his sheep wagon and Western artifacts, including his carvings. So, he and his new bride drove across the country to collect his wagon and other personal goods to haul back to Georgia.

‘Spectacular’ Ride

“Our rig was quite spectacular, I had a wooden platform on top of the car, and an elk head fastened to it, also a deer and a mountain goat,” Evans wrote in his memoir.

“I had bought them from a lady in Lewiston for curiosities to show the folks in Georgia. … At one point when we stopped for gas, a little boy came running up and asked, ‘Where are you putting on the carnival, mister?’”

Evans said while driving through heavy traffic around Shreveport, Louisiana, a woman in a Cadillac passed his rig, “sneering.” His new wife was self-conscious about their traveling rig as well.

“Pauline drew a long breath, ‘There goes a proud woman,’” Evans recorded her saying in his memoir. “‘I used to be a proud woman, too, she ought to marry a man from Wyoming. He’d take the pride out of her.’”

Wells said Evans and his great-grandmother’s house became a destination when he was young. One thrill was to stay the night in the sheep wagon.

“The sheep wagon had the white top and was green around the sides,” Wells said. “You’d go up in there and there was like a wood burning stove and a couple of bunks and a table to sit at. It was a lot of fun as a kid to stay in there.”

Wells characterized his great-grandfather as a “quiet” and “very gentle fellow” who loved reading Westerns, doted on his great-grandmother and was “probably one of the most easygoing people I’ve ever been around in my life.”

His Collection

In addition to his carvings, Evans also had a collection of Native American artifacts, his chaps, branding irons and other items from his Western beginnings that he kept for the rest of his life.

Evans’ brother Bob would go on to be a well-known artist and sculptor with pieces displayed around Casper and at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Bill Evans’ talents ran in the family, Wells said.

Wells said the carvings made by his great-grandfather, who died in 2001, mean a lot, but he feels a need to find a way to share them.

“I’ve got the sentimental attachment to him. I really would like to find a home for them where they could be displayed. Not just the carvings, but some of the other things,” he said.

“While I love having them and they are neat to see, I really feel like they deserve to be displayed and seen by a wider audience. It would feel great to me to be able to have him recognized in that way because he was just a neat person.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.