Dale Creek was only 2 feet wide and a foot deep as it snaked through southeastern Wyoming Territory in April 1868 when it became a major obstacle in America’s Manifest Destiny migration westward.

While hardly a raging river, the creek would need a bridge 650 feet long and 150 feet high for the Union Pacific Railroad to cross it and the gorge it carved that rose above the “clear as amber, pure as snow” water flowing some 20 miles southeast of Laramie.

An article in Nebraska’s Omaha Herald on Sunday, April 26, 1868, called the bridge a “miracle” of modern engineering and construction.

“Upon the highest summit where the Union Pacific Railroad crosses, spanning over it from cliff-to-cliff, a pine timber bridge, jointed, cross-tied, intertwined, self-supporting and perfectly secure,” the reporter wrote. “And all built within 85 days and ready for the heaviest trains.”

Union Pacific Museum Curator Patricia LaBounty of Council Bluffs, Iowa, agrees. The Dale Creek Bridge, the longest and highest the railroad would build, was an engineering marvel for its day.

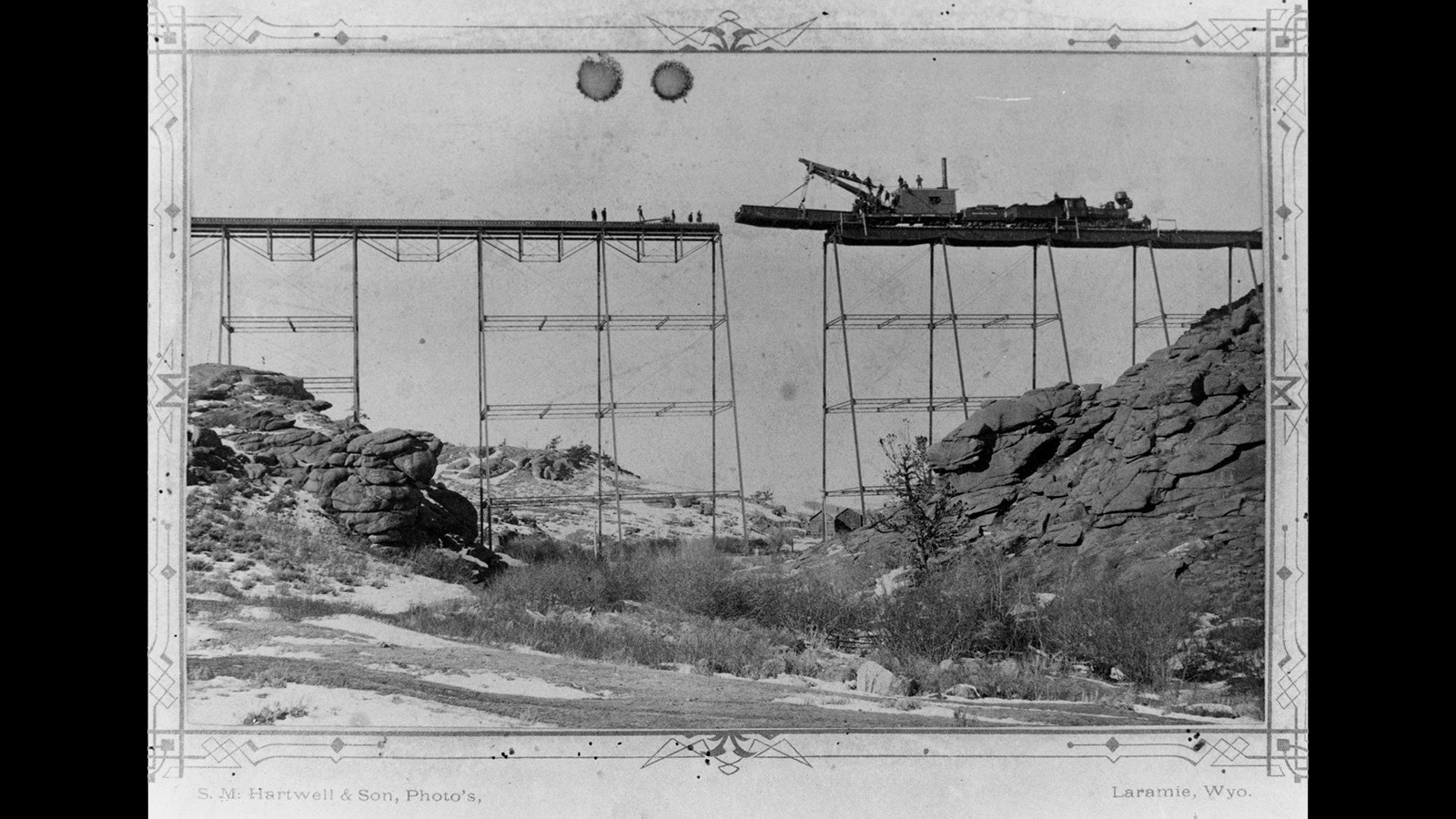

However, the structure that was initially pieced together by the Boomer Bridge Co. in Chicago, disassembled, and shipped to the location was not quite ready for prime time when the first train chugged onto its wooden trestle, she said.

‘Terrifying To Cross’

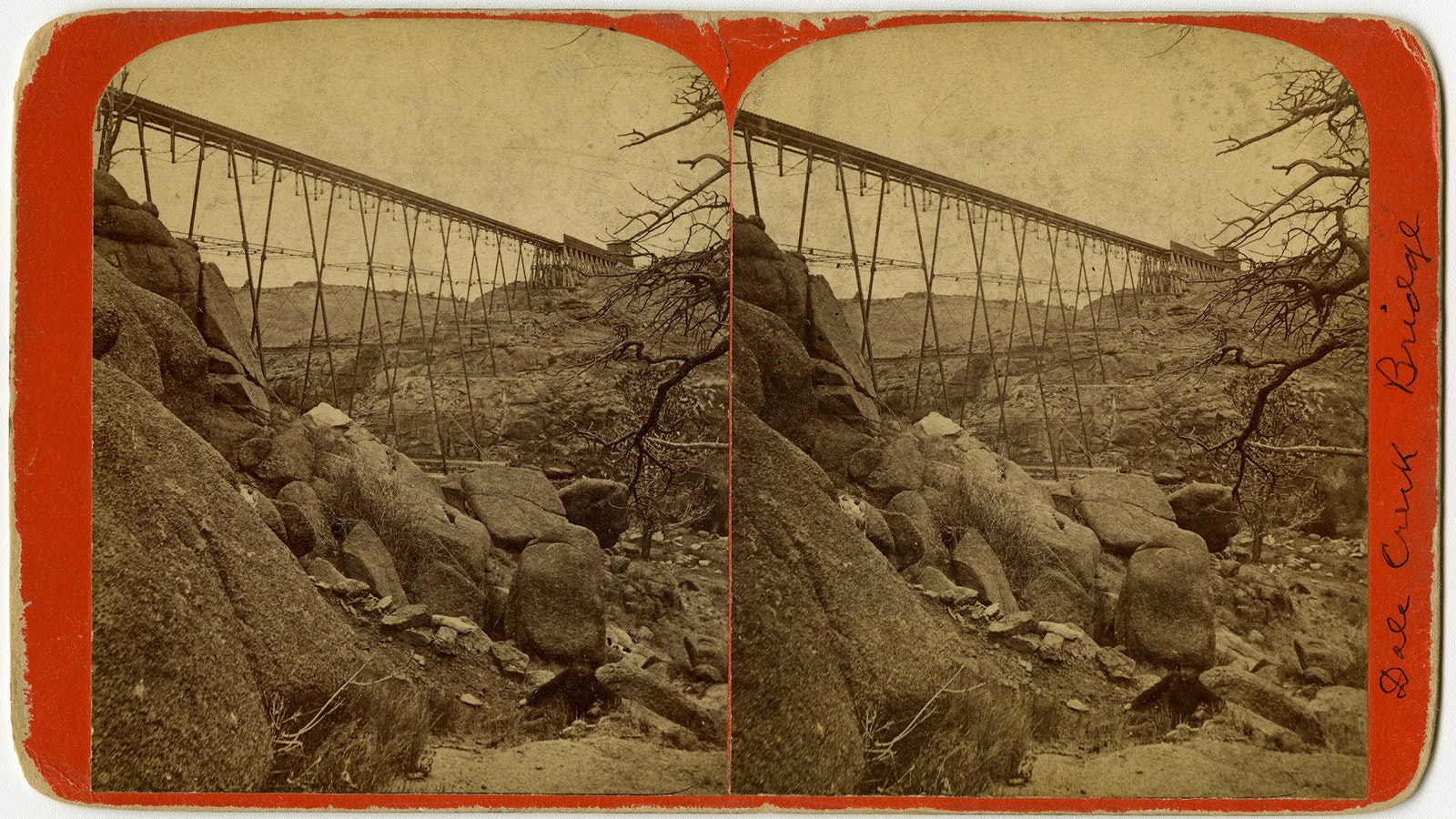

“At the scene, there were reports that this was terrifying to cross,” LaBounty said of the huge, steep and intimidating span. “It swayed in the wind, and it was literally terrifying. If you look at some of those photographs, the trains look precariously balanced on top of this skinny little trestle over this 100-and-some-feet distance to the bottom of the gorge.”

Indeed, the crossing was enough sober up the rowdiest of cowboys.

The location of the transcontinental railroad’s Dale Creek Crossing is now part of the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. On April 23, 1868, the day the Dale Creek Bridge was completed, the rail crews weren’t jubilant, they just didn’t want to die.

LaBounty said civil engineers employed by Union Pacific as it raced across the West to complete its section of tracks had a “lot of conversation about this portion of the line.”

The Transcontinental Railroad was an effort to connect the East and West coasts with a rail line. The Union Pacific laid track from Omaha, Nebraska, to Promontory Summit in what is now Utah, while other railroads laid track from Oakland, California, to Utah.

In the end, the Union Pacific Chief Engineer Grenville Dodge made the final decision that the railroad needed to cross Dale Creek and gorge.

“One of the engineers at the time made the comment that this was a lot of engineering for a tiny little creek (that) they were crossing,” LaBounty said. “But one of the biggest pressures of the time was that to construct a railroad, you have to obey some principles of engineering. You can’t have too many curves, you can’t have too steep of a grade, you really don’t want to cross too many places that you have to bridge or fill, and you don’t want to have too many tunnels.”

When the railroad made choices to build a bridge like the one over Dale Creek it was because “every other solution didn’t work out,” she said.

Wyoming Winds

At the time of initial completion, LaBounty said the “engineer on the ground,” Samuel Reed, watched the bridge sway and understood that design engineers had not accounted for the strength of Wyoming winds. Reed ordered that ropes be tied to bridge and anchored to gorge walls. Those ropes were replaced with cables as soon as they could arrive.

Early on, some locomotive engineers refused to stay in the cab and cross the bridge. They would let the train’s fireman take the controls while they walked the trestle, while the trains had to slow to 4 miles per hour to cross the span.

On at least one occasion, cowboys who partied a little too much decided to ride their horses across the imposing structure and its towering height to the other side. A letter in Union Pacific files from T.C. Rowley, the Converse County treasurer, dated April 25, 1934, told the story. Rowley wrote about a man named William Powell of Douglas who worked in a railroad tie camp on Sherman Hill not far from the Dale Creek Bridge in 1877.

“He (Powell) knew, and talked with five men, John Miser, Charley Fox, Jack Sharp, Sam Wittoe, and one of the Robbins boys, who rode across Dale Creek Bridge on horseback. They had been putting on a party and were pretty well boozed up,” Rowley wrote. “They said they were in a sort of daze when they started across, but when they got out on the bridge with just the planks in the middle and found they couldn’t turn back they sobered up right away.”

The bridge in different forms was in place from 1868 through 1901. The wooden structure lasted from 1868 through 1876. In 1876, the wooden structure was replaced with an iron one from the American Bridge Co. using the same foundational piers. The bridge was stretched to 707 feet long.

Spider Bridge

“Among the railroad (crews) it was called the ‘Spider Bridge,’ because it looked like a spider web,” LaBounty said. “When you look at the pictures, I think the iron bridge looks much more terrifying.”

On Nov. 30, 1884, the Chicago Tribune reported that a fire started by tramps had burned the “12 feet of wood” that remained as part of the iron bridge and that passenger transfers across the gorge were being made by wagons.

The metal bridge had to be modified several times to accommodate heavier trains. In the early 1900s, the railroad for several reasons decided to change the route and lay track south of the bridge location. Steam shovels at the time were able to fill deeper areas with rock and dirt, and tunneling was easier as well. Railroad tycoon Edward Henry Harriman was trying to create efficiencies.

An article in the Laramie Daily Boomerang on Oct. 26, 1898, announced the new route chosen by Union Pacific engineers.

“This new line begins at a point three or four miles south of the Dale Creek Bridge on Dale Creek and runs thence to Laramie and Cheyenne,” the newspaper reported. “This route does away with the high Dale Creek Bridge and will be an economy in time, in consumption of coal, in the expense of the bridge and its watchman, and in the danger attending the operation of the road with the heavier grade.”

The railroad moved its line south to Hermosa, Wyoming, and the bridge was dismantled. In 1946, five girders recovered from the Dale Creek Bridge were used in other bridges around the Union Pacific system, LaBounty said.

The railroad museum curator characterizes the Dale Creek Bridge accomplishment a symbol of the “can-do attitude” that existed in the nation as the Transcontinental Railroad was built.

“It’s a testament to that indispensable will to make something happen. Failure wasn’t even considered,” LaBounty said. “Once a decision was made, and a direction was set, (failure) didn’t even enter into it. It was, ‘How are we going to accomplish this?’ Not ‘if.’ I think to me, that is what some of these engineering structures speak to us now.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.