Readers will inevitably take sides with this story. There will be outrage. Decidedly, animal rights activists for sure will howl with rage.

The intent is not to spark debate or rekindle old controversy. What’s done is done, live and learn. In many ways, we are a better-informed and better-behaved society than generations past. In other ways, not so much.

This trip down memory lane is not a time-machine “make good” to fix something from our sketchy past. No cancel culture. No statue teardowns. No excuses.

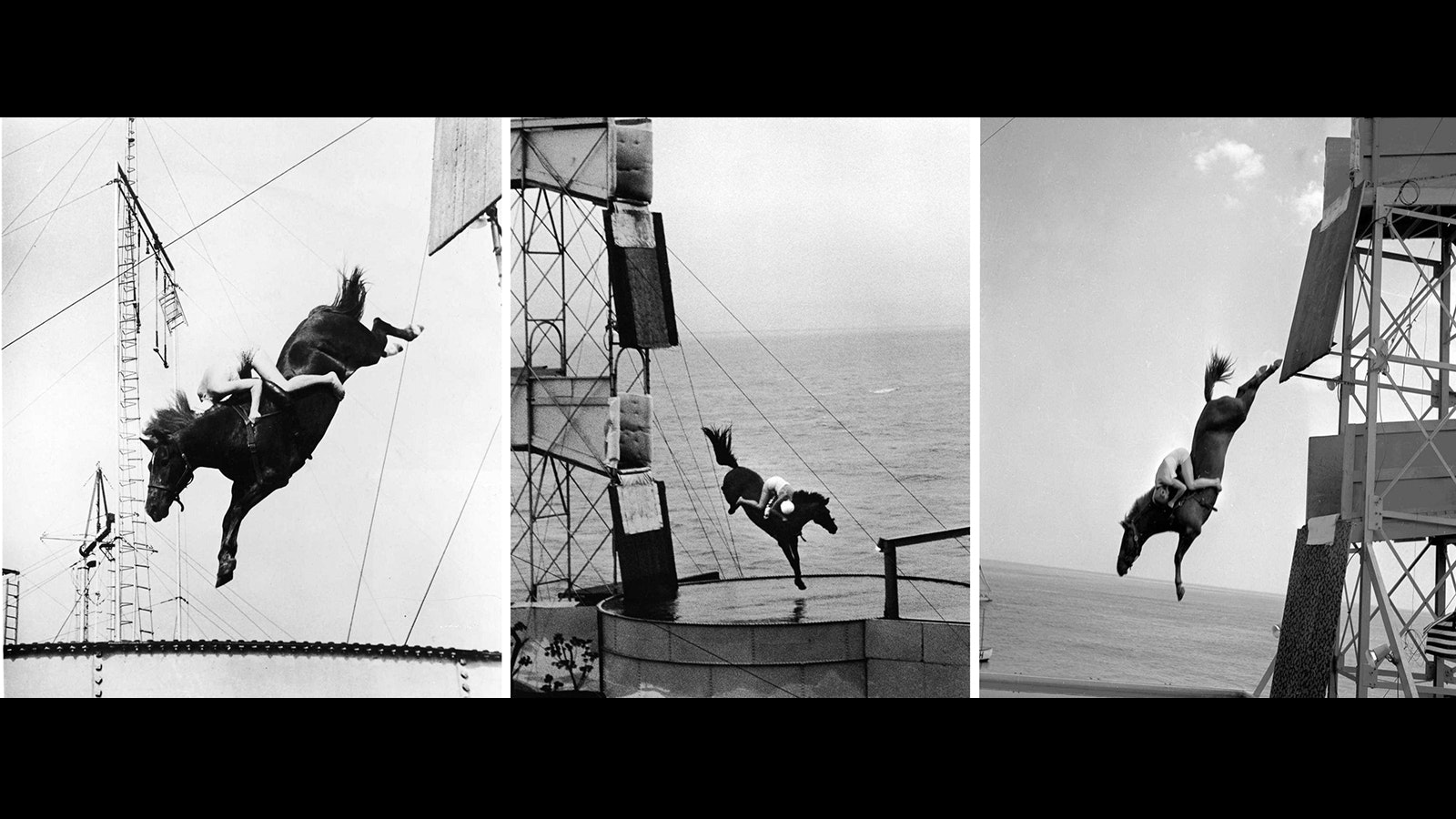

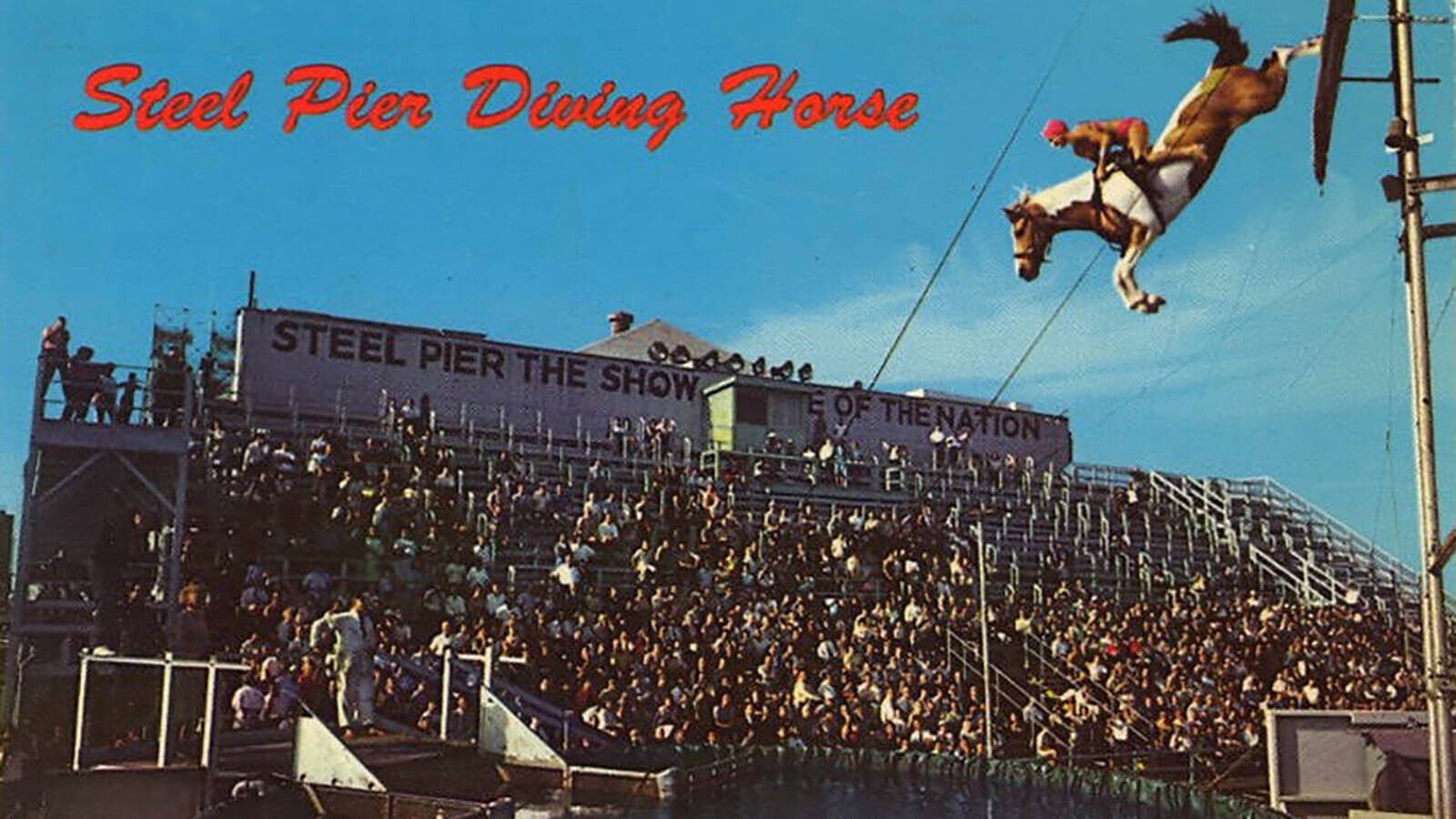

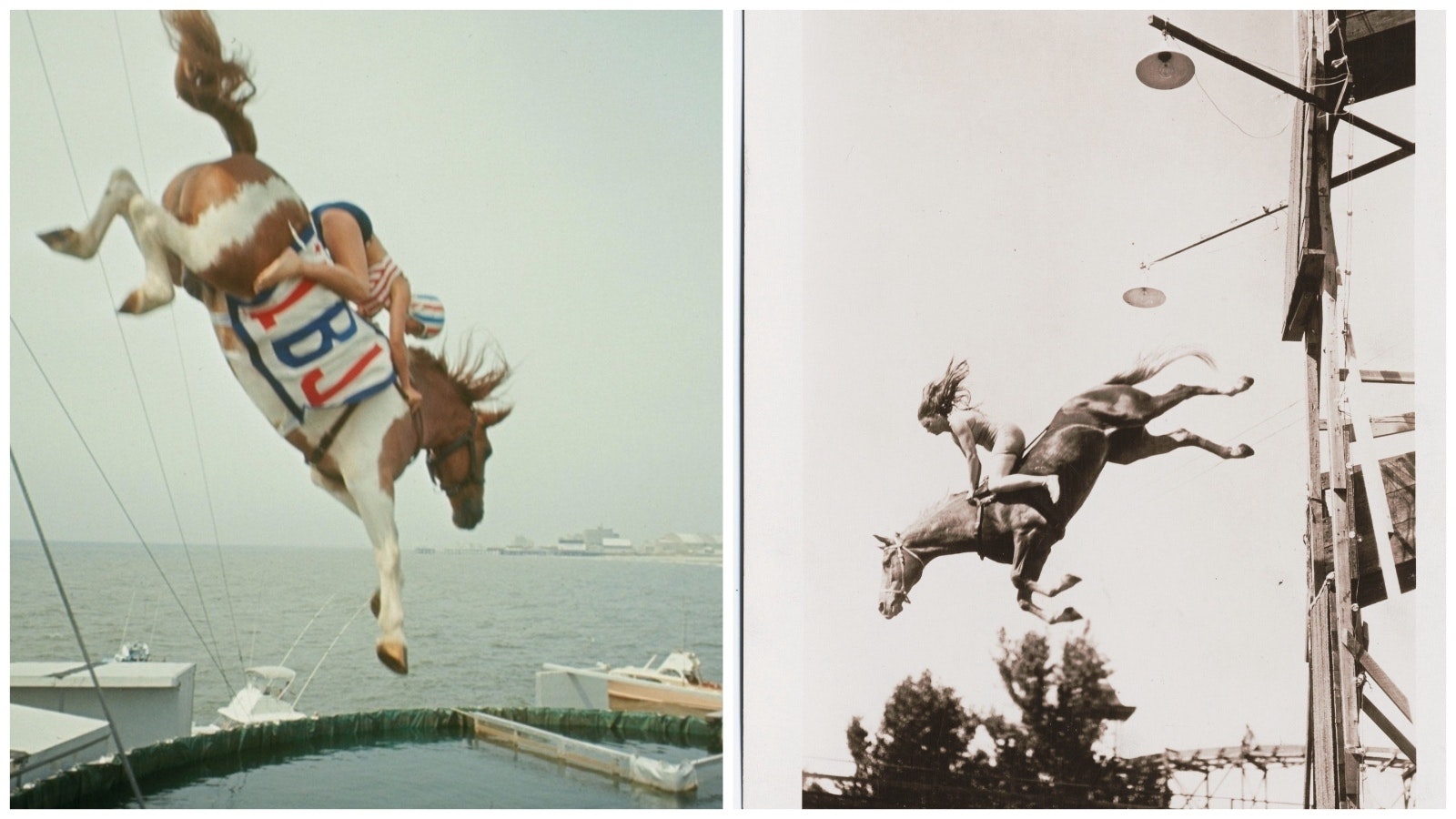

Let’s own our past and simply marvel in the fact that for 100 years we were entertained by diving horses. Yes, horses that launched themselves from 60-foot wooden scaffolding into a shallow tank of water. For our amusement.

The spectacle that began in the U.S. in the late 1880s riveted audiences from New Jersey to Texas to Wyoming for a century. Peaking in the 1920s when the traveling sideshow found a permanent in-residence home in Atlantic City, horse diving seems like a tall tale granddad might embellish after a few too many highballs.

But it was real. The highlight attraction of many a state and county fair. How starved must people have been for distraction before cable TV and the internet?

So many questions.

Who thought this up? Who in their right mind would get on a horse and plummet toward a piddling pool below? How many deaths did this cause? How many injuries? All for the titillation of the general public and the livelihood of a few shyster showmen.

Bring your curiosity. Leave your condemnation.

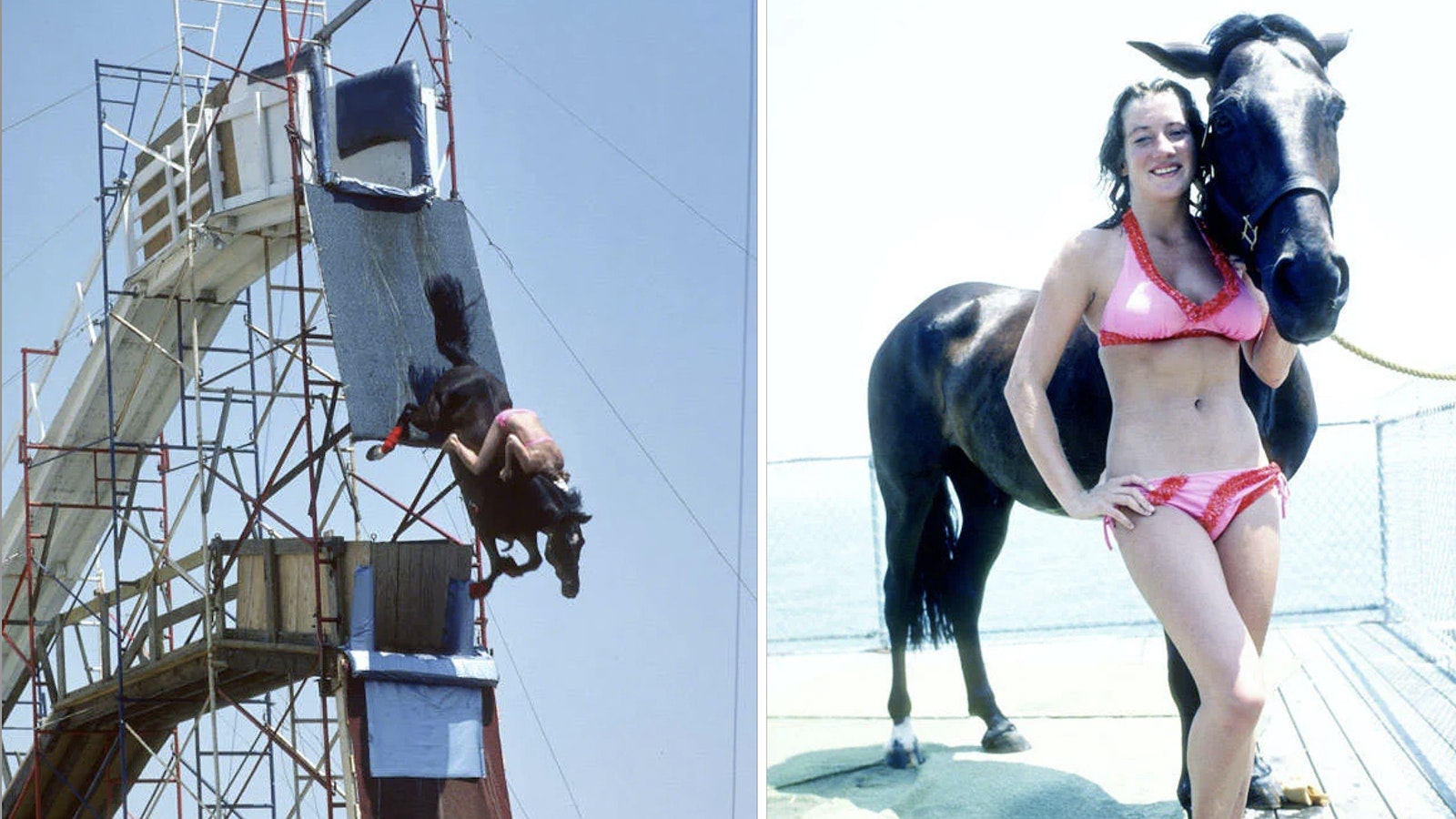

This is a memoir of epic screwball proportions. That horse with a bikini-clad damsel on its back is plunging toward earth, aimed like an arrow straight for a big splashdown. How does this not end in disaster?

You can’t NOT look.

Humble Beginnings

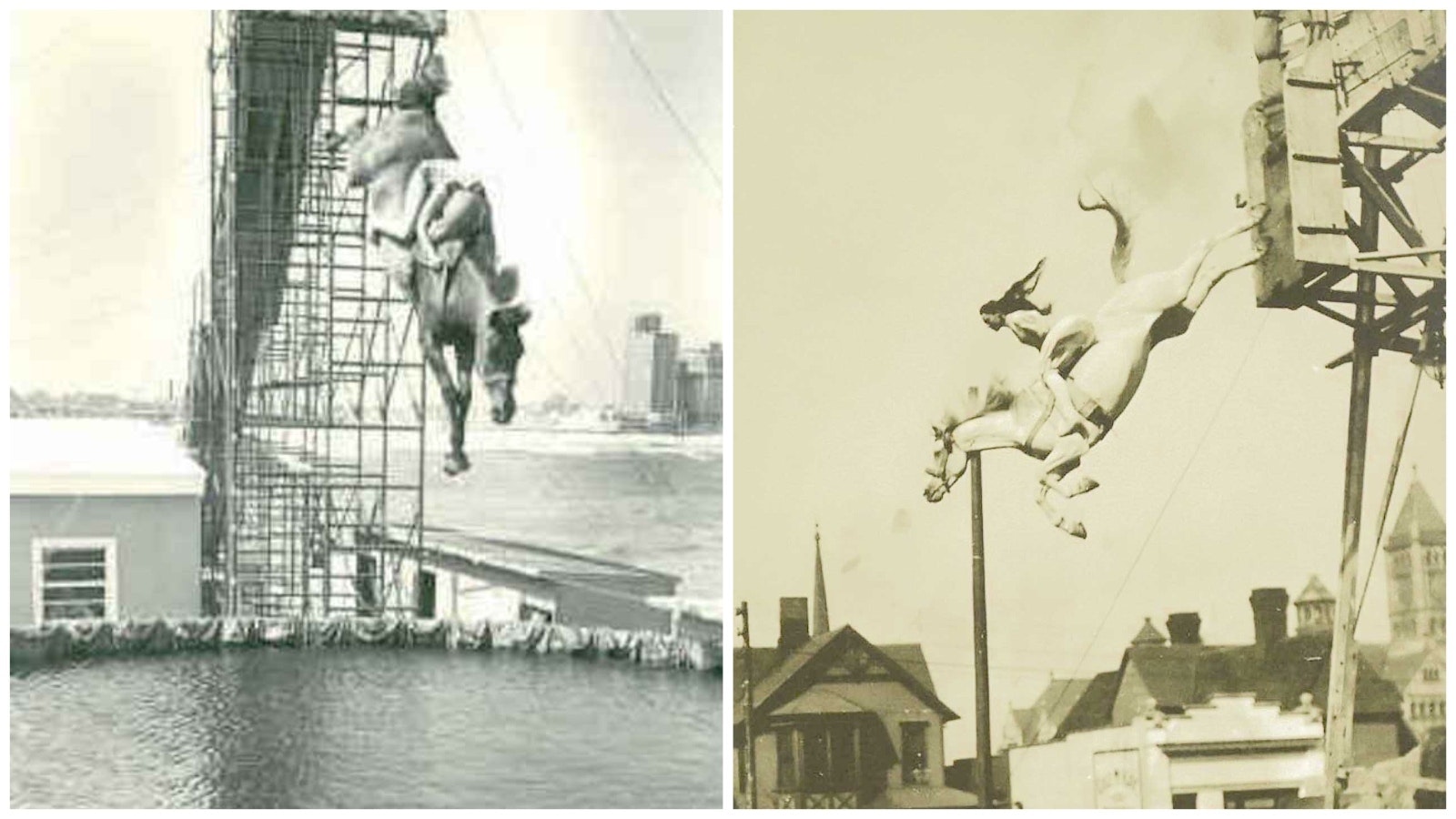

Horse diving was probably inevitable, a product of the times. After all, the late 19th century brought all sorts of bizarre entertainment to a fledgling nation still literally mapping out its homeland.

Diving horses seem to fit right in with traveling circuses, freaky sideshows and boxing kangaroos. It had to be a nightmare time for the ASPCA (f. 1866) for sure. But were horses truthfully mistreated or abused in the practice of diving? More on that later.

It was William Frank “Doc” Carver who gets credit for popularizing the “sport” of horse diving. He wasn’t the first to offer it to the public, but he was its most successful pitchman.

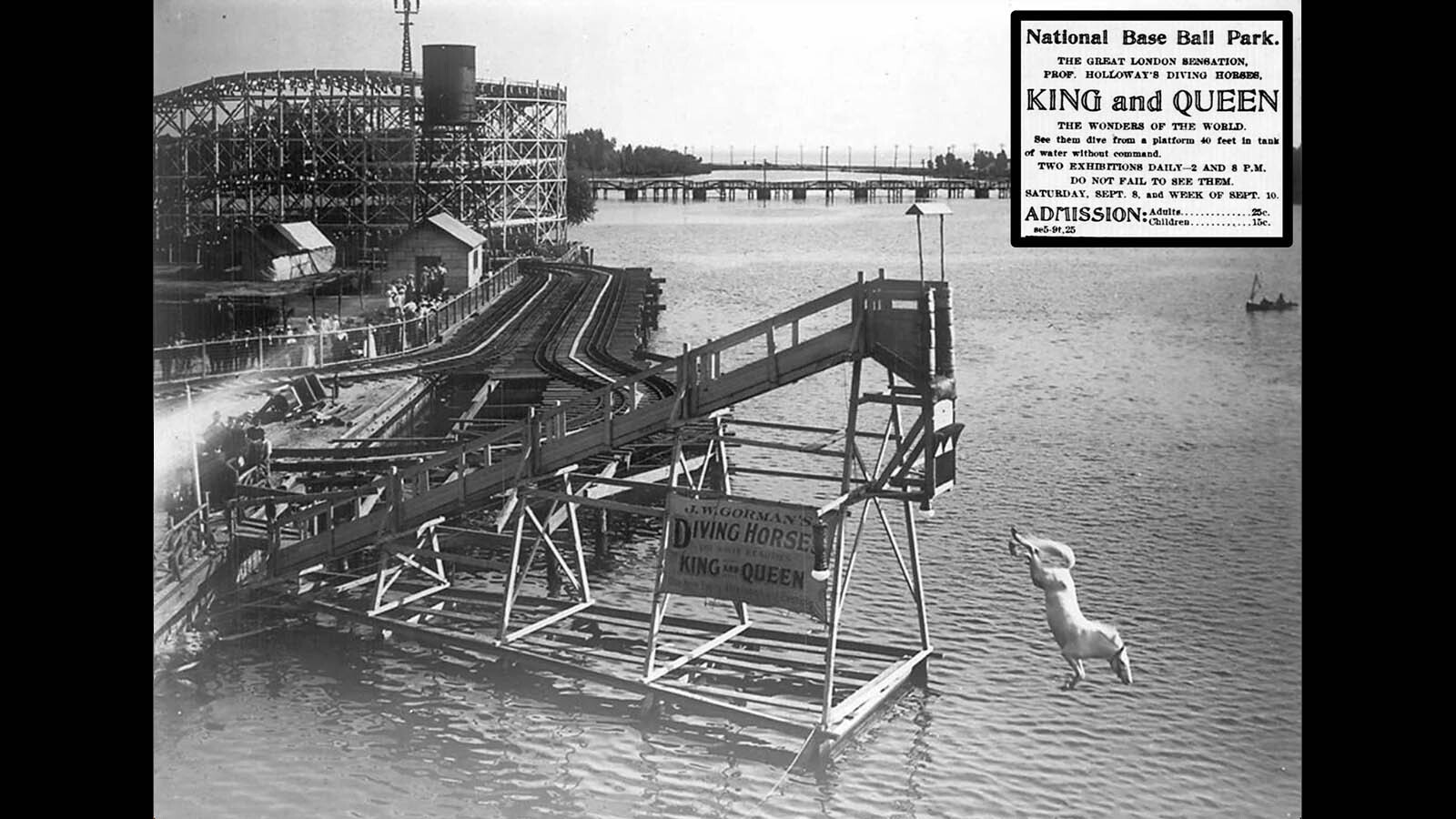

It was an Iowa horse breeder named George Holloway who first introduced a pair of milk white Arabians with the astonishing ability to jump from great heights into any body of water. Holloway claims he stumbled upon the discovery when as just colts, he noticed King and Queen leap off a bluff on his ranch and into the Des Moines River to join the rest of the herd that included their mothers.

Holloway eventually trained the water-loving horses to perform this trick from a constructed platform. By 1899, the show hit Shoot the Chutes pond at Coney Island where famed inventor Thomas Edison even filmed it. As the act’s notoriety grew and a reported tens of thousands paid to see it, Boston promoter J.W. Gorman bought the horses in 1901 and ramped up their tour schedule.

Not even a declaration from the American Humane Society in 1900 stating that “making horses dive was cruel” would slow the sensation that was billed as “J.W. Gorman's High Diving Horses Show." It was featured in parks throughout the Northeast, Canada and even London in 1902.

Holloway tried to train at least 85 other horses to perform the same high diving act, but he never could get any to do it the way King and Queen did — pointing straight down like an arrow as a human would dive. Every other horse kept its head up and belly-flopped.

Carver Adds The Girl

As popular as King and Queen became, no one had thought to add a rider to the daredevil stunt — until Doc Carver.

Carver was the prototypical showman of the era. Larger than life and rarely truthful about anything, including his own birthdate and the legitimacy of his offspring.

Carver claimed to have been born in 1840 for him to better perpetuate a self-spun narrative that he grew up with the Santee Sioux Nation in Minnesota.

Carver migrated west by 1872 and briefly practiced dentistry (hence the nickname “Doc”) at Fort McPherson in North Platte, Nebraska. It was there he first met Buffalo Bill Cody.

The two would eventually start up the Wild West Show that Cody is known for, but after a few years they had a bitter falling out and Carver struck out on his own. The expert marksman would eventually try several different iterations of a Wild West show of his own, even touring Australia for a time in the 1890s.

By 1894, Carver was dabbling with a horse diving exhibition using a sleek, compact mare named Black Bess. It did well and was the talk of St. Louis, where he first debuted the exhibit. But it wasn’t until he put a girl on the horse that the act really took off in 1906.

Carver’s original diving diva was a woman named Lorena Lawrence, who Carver later claimed was his own daughter. She would eventually take the last name Carver. Carver’s son, Al Floyd, who some say was adopted, was the horse trainer and builder of the scaffolding.

American audiences couldn’t get enough of the daring high dive. Before long, Carver had two distinct teams totaling six horses performing east and west of the Mississippi.

Horse Diving In Wyoming

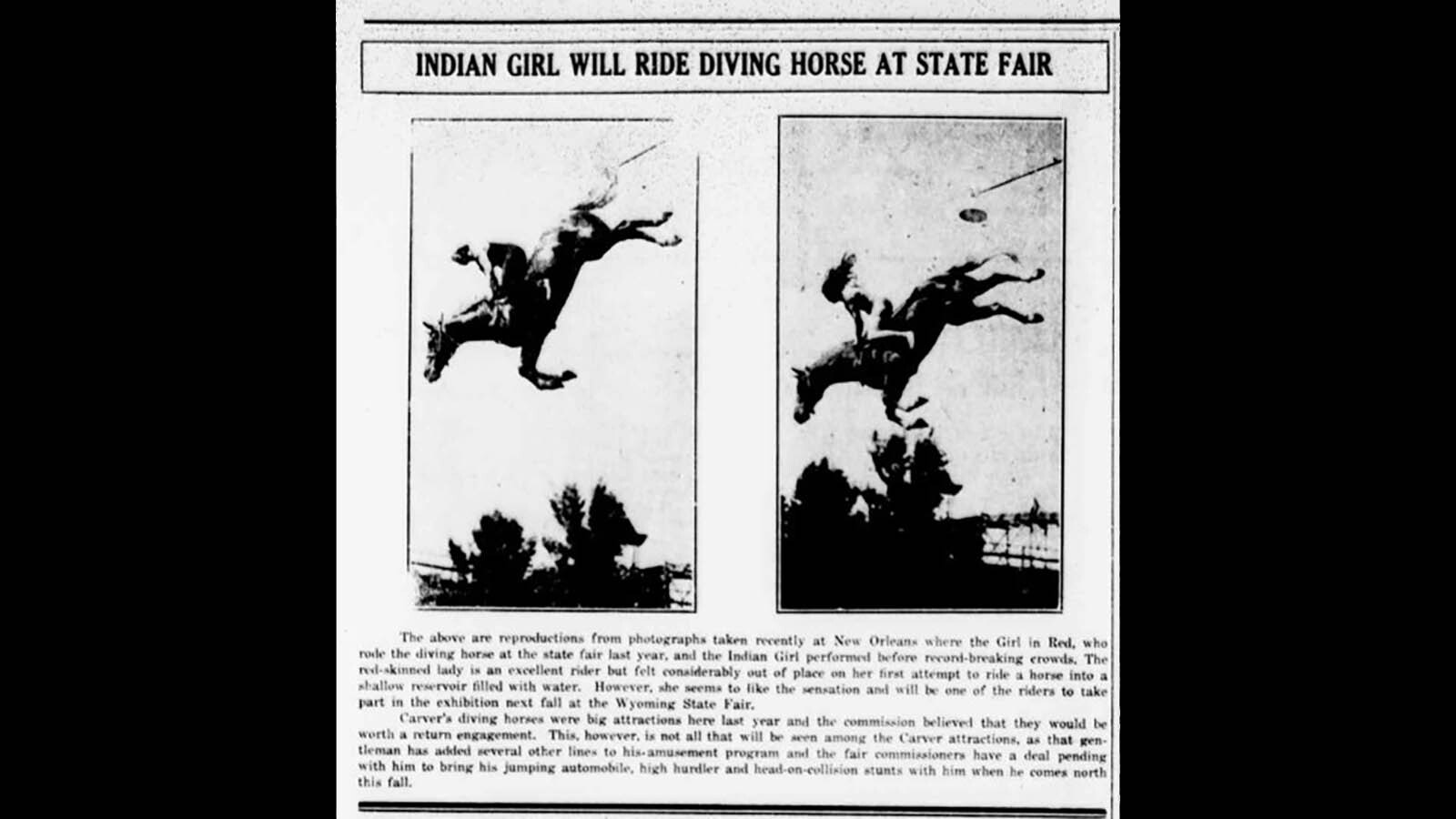

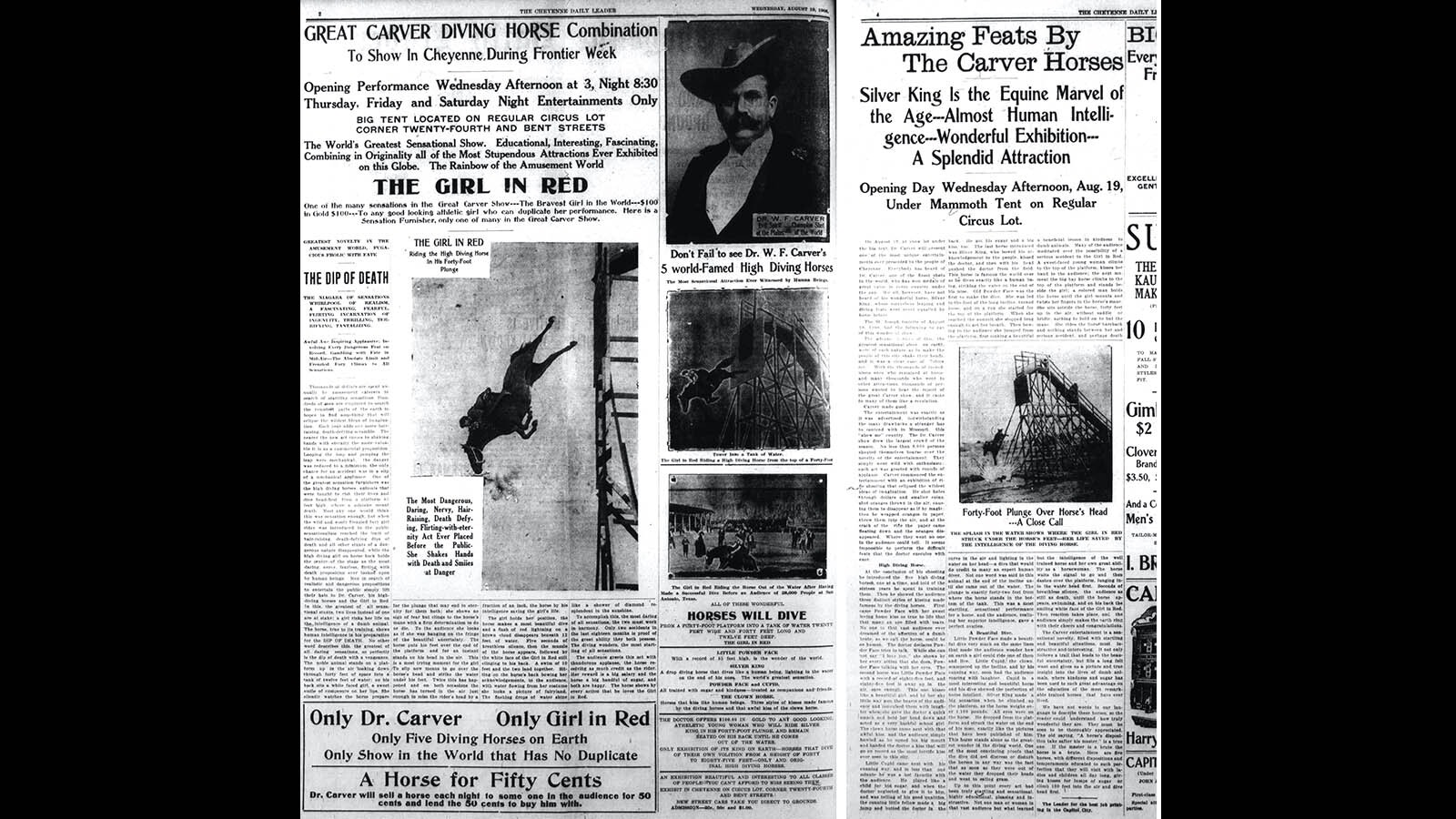

The show eventually made its way to Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1908. Billing it the “Dip of Death,” the Cheyenne Daily Leader claimed “no less than 8,000” were in attendance to see Carver put on a shooting demonstration before the horse diving.

“Many of the audience meditated over the possibility of a serious accident to the Girl in Red. A sweet-faced young woman climbs to the top of the platform, kisses her hand to the audience; the next moment the big bay horse climbs to the top of the platform and stands beside the girl,” the paper stated Aug. 20, 1908.

The Girl in Red (likely Lorena) was the top-billed human star of the show.

“[T]he girl mounts and twists her fingers in the horse's mane. She sits astride the horse, forty feet up in the air, without saddle or bridle, nothing to hold on to but the mane. She rides the horse bareback and nothing stands between her and serious accident, and perhaps death,” the Leader added.

The horses themselves quickly gained more fame than the riders. Silver King was the 1,100-pound quarter horse that “dove headfirst like a human being.” Little Powder Face was the world record holder with an 85-foot dive (likely an exaggeration).

There were also Gamal, Lightning and Klatawah, the horse known for his theatrical nature.

Klatawah was a prima donna, Lorena would tell reporters. The larger the crowd, the more the star gelding would delay his jump, pawing and tossing his head with dramatic buildup. If the crowd was scant or it was a rainy day, he would be noticeably sulky. He once backed all the way down the ramp when he didn’t feel like jumping.

As with many of his early shows, Carver offered $100 in gold to any “athletic young woman who volunteered to ride Silver King in his 40-foot plunge.” No one took him up on it that day in Cheyenne.

Incidentally, though, a plucky young lady did take Carver up on his offer and reportedly had to sue to get the brash promoter to pay up. Eunice (Winkless) Hadfield accepted the dare and rode Silver King straight into the water tank from 40 feet on July 4, 1905, in Pueblo, Colorado.

Carver’s horse diving show would return to Wyoming for a show in Lander in 1916 and for the 1917 state fair in Douglas. A more local act — Ardmore the Diving Mare — also performed 35-foot dives at the Sheridan County Fair in 1914.

Roaring Twenties

By 1919, Gorman’s act with King and Queen began to fizzle, but Carver’s novelty was just picking up steam and poised to usher in its greatest name.

Sonora Webster grew up in Waycross, Georgia. She was just crazy about horses. In her book, “A Girl and Five Brave Horses,” Sonora admitted to skipping school now and then for the opportunity to ride. She even once tried to sell her brother for a horse when she was 5.

At age 19, Senora answered a newspaper ad looking for “an attractive young woman who can swim and dive; likes horses; desires to travel.”

She got the job and was soon off to New Jersey where she said, “After a couple of days of training I was black and blue all over and so sore I could hardly move.”

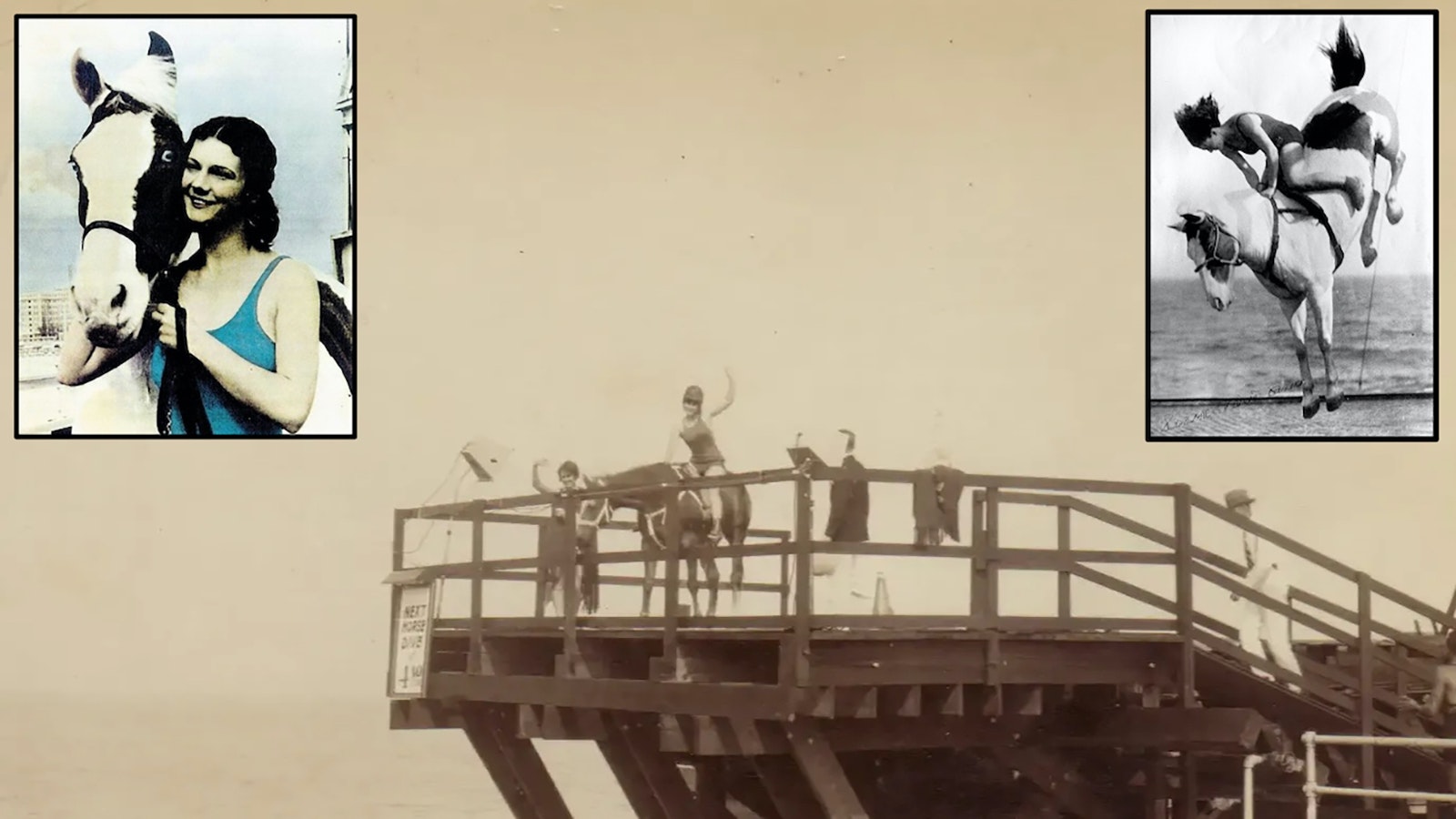

On May 20, 1924, Sonora Webster made her first public dive off a 40-foot tower at an amusement park in North Carolina. The new “Girl in Red” was born. Sonora performed anywhere from two to five times daily. For that, she made $125 a week — much better than the $15 a week she made at her previous gig as a department store bookkeeper.

Sonora would ultimately marry Carver’s son Al, the man who trained the diving horses. The two wed in October 1927, just two months after the death of Doc in August of that year.

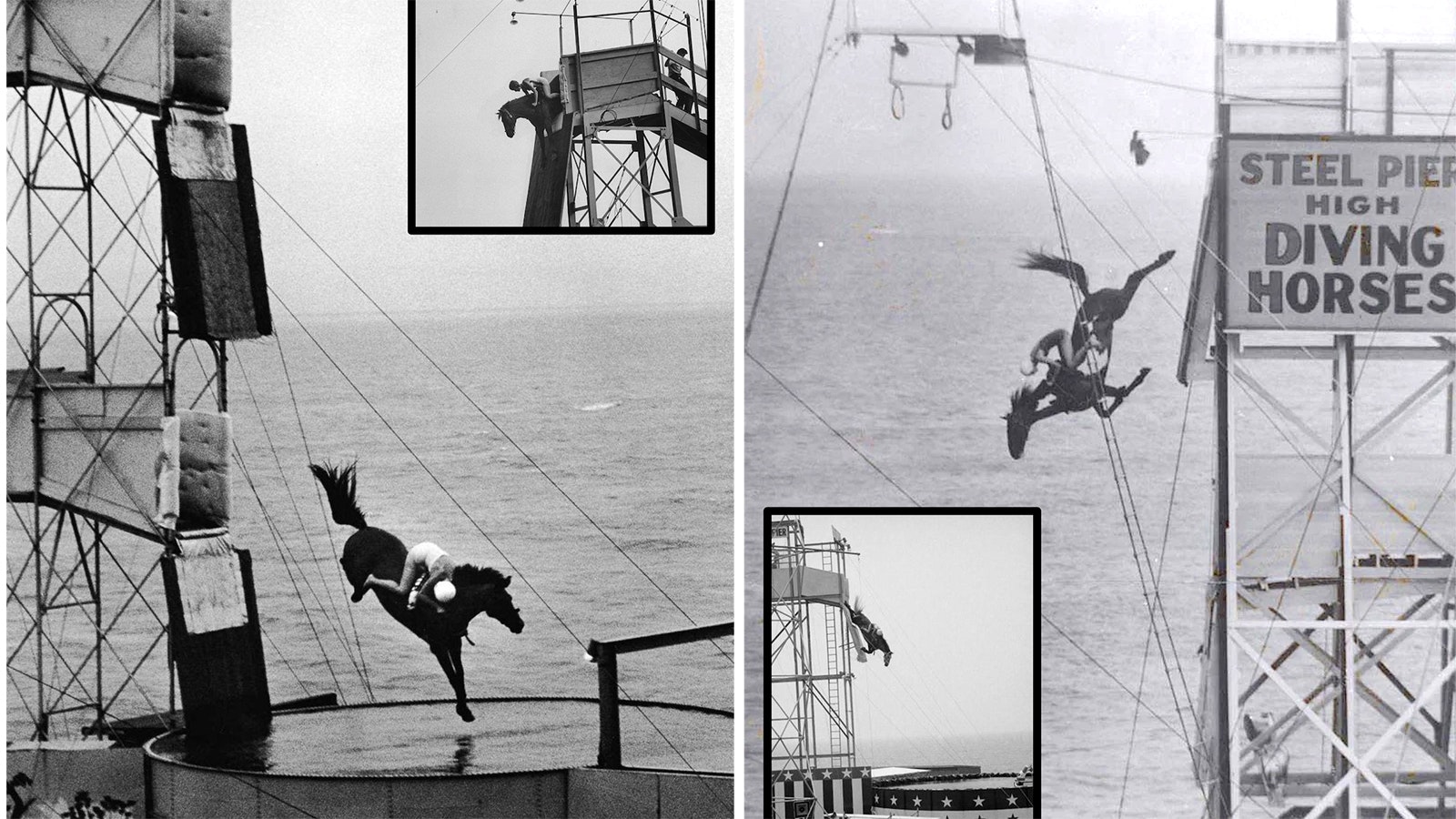

The following year, 1928, the traveling show hit the big time. From its humble beginnings in circus tents and state fairs, Doc Carver’s Diving Horses became one of the main attractions on the world-renowned boardwalk at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

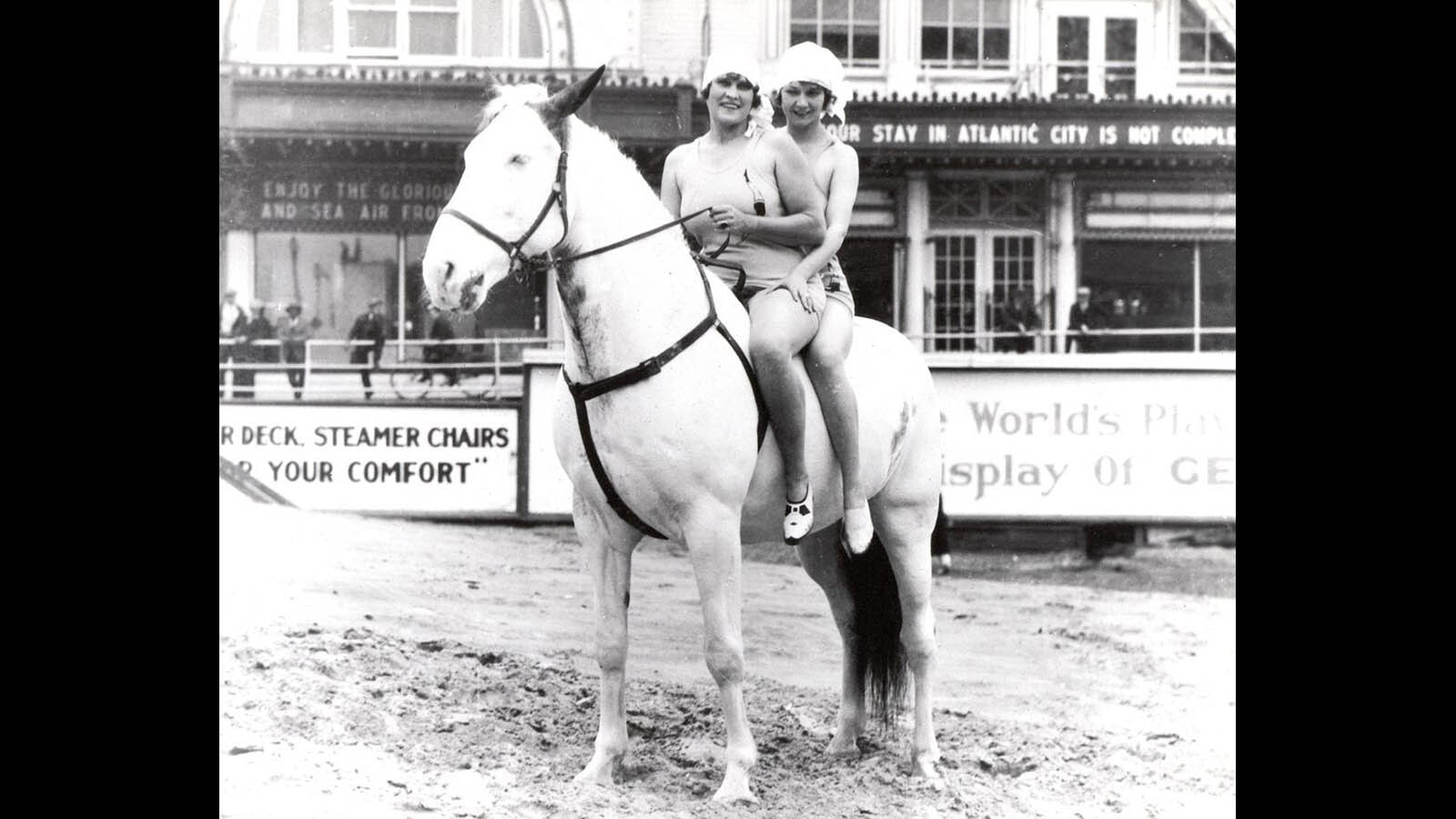

Crowds would flock to see the death-defying performance for decades. Sonora’s sister, Arnette, was hired on as an additional rider. She was just 15 and would dive with sibling Sonora until 1935.

A 19-year-old Jackie Carvan was also with the Carver crew briefly in 1923. Her practice dive made a rare British film reel.

Just how popular was horse diving at Atlantic City?

On the footings of Atlantic City's Steel Pier was mounted a tide gauge device that would measure changes in sea level of the Atlantic Ocean. Measurements kept from 1928 to 1978 indicated higher tides and sea levels during the years the diving show was in its heyday. From 1945 to 1953, when the horse diving show was on hiatus from the pier, tides and sea levels were mysteriously lower.

Officials found out only later that the weight of the immense crowds flocking to the boardwalk’s grandstands to see the horse diving show was causing the pier to settle slightly in the soft, sandy bottom, giving misleading readings.

More On Diving Diva Sonora

At the height of her fame, Sonora met with tragedy one fateful day in 1931. During a dive she had done flawlessly hundreds of times on a pinto horse called Red Lips, Sonora was nearly killed.

Something wasn’t right from the beginning of the jump, Sonora recalled. Red Lips was off-balance when he left the platform. Sonora tried to throw her weight to the front of the horse to help it hit the water correctly. In doing so, Sonora was unprepared for the impact.

Riders learned to tuck their heads along the side of their mount’s neck as they landed in the pool below. In this case, Sonora hit the water face first with her eyes open. The impact detached both her retinas, causing her to lose her sight for the rest of her life.

Undaunted, Sonora made a comeback less than a year later. It wasn’t pretty, but she persevered, performing her dives as before for another 11 years.

“Four times I missed the horse entirely,” Sonora disclosed in her autobiography.

When World War II put a damper on the show in 1942, Sonora retired and moved to New Orleans with her husband. She took a job as a typist and became active in causes for the visually impaired.

Her life story was immortalized in the Disney film “Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken,” released in 1991.

Sonora died Sept. 20, 2003, in Pleasantville, New Jersey. She was 99.

Below, watch a rare clip of Sonora diving on her horse Red Lips:

The End Of An Era

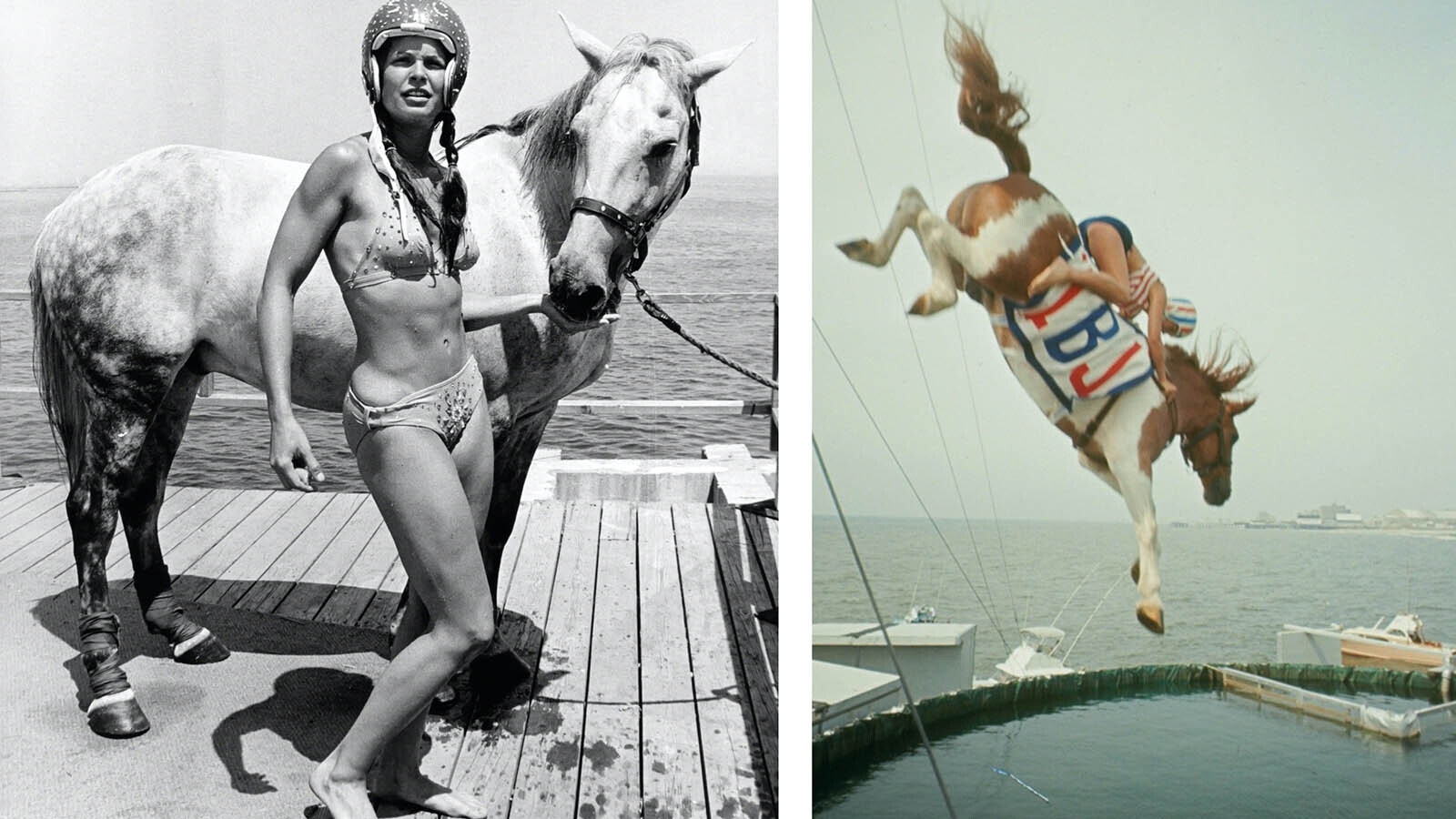

Lorena Carver (Lawrence) took the diving horses show overseas to Europe shortly after World War II with the Steel Pier also partially ruined by a hurricane in 1944. The show floundered there and was brought back to Atlantic City in the mid-1950s, where it ran there for another two decades.

The final horse dive show was performed on Labor Day weekend 1978. Crowds were already thinning throughout the ’70s and animal rights groups made it all but impossible to continue profitably.

It was a “merciful end to a colossally stupid idea,” then-president of the Humane Society Wayne Pacelle told Reuters.

An attempt to revive the act using mules in 1993 failed. Steel Pier owner Anthony Catanoso briefly floated the idea of bringing horse diving back to honor history in 2012, but the notion was shut down by a change.org petition.

Horse diving has more recently continued in diverse places to little fanfare and fierce protest.

The Lighting Ranch in Pipe Creek, Texas, featured “Smokey,” a star cast member of the ranch’s Aqua Mules, that climbed a ramp at every Saturday night rodeo as recently as 2009 to jump in a tank of water without a rider.

In Lake George, New York, Lightning the Wonder Horse made twice-daily riderless plunges from 10 feet into a 117,000-gallon pool of water at the now-defunct Magic Forest amusement park. That act was finally shut down in 2019.

Training And Caring For Diving Horses

Informed and enlightened minds of 2024 who formulate and share their expert opinions on Reddit and TikTok are quick to bash diving horses as a barbaric form of entertainment. Cruel at worst, exploitive at its best. But bonneted ladies and top hat wearing gents of 1924 did not possess the perfect hindsight of 2024.

A lot of what passed muster a century ago would not fly today. And pretty much everyone involved in the sport of horse diving — from the early legends like Lorena, Sonora and Arnette; to later stars like Barbara Gose, Annie Eastham Miles and Sarah Hart — say the same thing.

The horses were never forced to dive, and all acted like they enjoyed it, they say. Everyone involved in the sport has adamantly defended it and the treatment of the animal athletes.

“Wherever we went, the SPCA (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) was always snooping around, trying to find if we were doing anything that was cruel to animals. They never found anything because those horses lived the life of Riley,” Arnette French once said in an interview.

“They were very well kept. They would ride the horses on the beach in the morning and they loved to go in the water and run along the waves. We didn’t keep them if they didn’t like the water,” said Hart, who dove horses in the late 1950s.

“I would have noticed if there had been anything unkind because I love animals. They were never in any way hurt or disrespected. In fact, they were taken care of better than the riders were. When I exited the tank, someone would bring me a towel, but it was the horse that got the blanket. The horse was always the star,” Hart added.

Lorena said her horses loved jumping so much, it was all she could do to hold them up on the platform for even a few seconds to build suspense before diving.

Sonora was also quoted as saying she never encountered a situation where her horse was forced, coerced or otherwise persuaded to jump.

“That would have put me in a very dangerous situation up there, and I would have never tolerated that,” she said.

Industry leaders often made the claim no horse was ever seriously hurt or killed in a century of the sport. Not so of the equines’ human counterparts.

Noted Atlantic City historian and author Vicki Gold Levi stated broken bones and bruises were common among the lady riders. Records on horse injuries were not reliably kept, but about two human injuries per year were recorded during the show’s 50-year run at Steel Pier.

Nonetheless, at least one horse and one rider were killed performing the stunt of diving.

On Feb. 17, 1907, in San Antonio, rookie rider Oscar Smith plunged to his death on his first ever dive. The 19-year-old Coloradan was filling in for the Girl in Red (Lorena Lawrence) who was reportedly “indisposed” at show time.

The crowd cheered as Smith and his horse made a perfect dive. But the cheers turned to nervous murmuring when the horse surfaced and exited the pool with no sign of Smith.

Bystanders jumped into the tank and pulled Smith’s lifeless body from the water. He never regained consciousness.

Carver said the kid likely suffered a heart attack in midair. An attending physician noted a bruise over Smith’s left eye and speculated he was probably kicked by the horse. No autopsy was ever performed. Carver paid to have Smith’s body shipped back to his family in Glenwood, Colorado, and the show went on the following weekend.

Twenty years following the death of Smith, it was a horse that would meet its end while practice diving in California.

One of the Carver’s favorite horses, Lightning, was drowned at sea while practicing a riderless dive into the Pacific Ocean at Lick Pier in Venice Beach.

On July 2, 1927, Lightning dove from a 40-foot tower into the ocean. He became confused and swam out to sea rather than back to the beach. A half-dozen lifeguards used flotation devices to bring the horse to shore. The animal could not be resuscitated.

Would It Fly Today?

A Wyoming horse trainer and a large animal veterinarian weighed in on the viability of horse diving and the challenges of safely performing the stunt today.

Horseman Kevin Meyer starts colts and trains horses for a living outside Douglas. He grew up working on a cow/calf operation in southeast Wyoming and today is a highly respected cowboy with a background in both the traditional working ranch and performance/show disciplines of the equine industry.

“Well, I don't claim to be an expert on horse diving, but the way they trained them 1880 was probably a lot different than the way they trained them in 1980,” Meyer speculated. “They probably forced them a little more in the beginning, shoving them off ramps until the horses became more comfortable to the point they would slide down ramps into water themselves.”

Meyer added that there is a horse for every job, and vice-versa.

“Horses are pretty amazing animals. You can teach them to do just about anything,” Meyer said.

But not every horse can be a diving horse.

“We have an old horse here on the ranch who is the brokest horse in the world. You could do dressage on him. But if there is a body of water, even an irrigation ditch with ankle high water in it, he will leap it like he’s jumping a 6-foot fence,” Meyer said. “Even if it’s something he’s crossed a hundred times before, when it is the first crossing of the day, it’s always a long jump event.”

But water is not an inherent fear for horses. Meyer said horses are not naturally hydrophobic and most are very good swimmers.

When asked whether he felt the high-diving line of work was abusive, Meyer pointed to other uses of equine and pondered which might be more of a hardship for the horse.

“Once the horse is trained to do it, I don't know how cruel this really is. Let’s say they have to do it three times a day for a summer. It’s the same argument as rodeo stock. Those bucking horses work 10 minutes a year, total,” Meyer said. “As long as it is not something hurting the animal, and if the horses are not trained cruelly, I wouldn’t have a great concern.”

Compared to other beasts of burden under the yolk for 25 years pulling a plow or wagon, Meyer brings up a point often argued by advocates of rodeo, horse diving and other potentially exploitative equine practices. What type of horse is truly living its best life, if any?

Still, critics of the novelty act say despite any loving care horses may receive, they certainly would not choose to leap into water from great heights on their own. They have to be coerced in some way by carrot or stick.

Longtime veterinarian Jim Theis, who recently retired from Ark Animal Hospital in Casper, said he has heard of horse diving from days gone by but never saw it. He worried about a broken leg if the horse landed wrong or if the water was shallower than, perhaps, 10 feet and they could hit the bottom.

“There is always the danger of a horse going over backwards, I suppose, if he balked on the platform or something like that,” Theis said. “Horses also do not have great depth perception with their eyes on either side of their head. So, maybe, if they did not turn their head sideways and look down, they may not really know just how high they are.”

Horses in diving acts across the country usually jumped from heights of 20 to 40 feet. The two platforms at Atlantic City were 40 and 60 feet initially, but reduced somewhat during the 1950s-1970s. The water tanks were usually 10, 12 or 14 feet deep and often lined with padding at the bottom.

By comparison, the highest high-dive competitors will dive from at this year’s 2024 Olympics is 33 feet into a 16-foot pool.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.