As a young boy living in Casper in the late 1980s, Kenneth Goehring would sometimes hear the phone ring in the late morning.

His dad, Dennis, who worked at the Amoco oil refinery turning crude oil into gas, diesel and other products, would be on the line. Dennis would let his son know he was about to pull a handle that would result in three steam whistles sounding off at slightly different pitches.

“My dad would call me and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to go over and blow these at noon.’ And as a kid, I would step out on to the porch and listen to him blow them,” he said.

And that for many years is how Casper residents knew it was time for lunch. It was a loud, steady, familiar call-out to the whole community, not just these working at the refinery.

For much of the 20th century beginning in 1914, the Standard Oil of Indiana refinery was a dominant presence in Casper visually and audibly. In 1922, the refinery was turning Wyoming crude into gasoline at a rate that topped the volume of other refineries in the world.

It began with an 84-acre land buy south of the North Platte and grew to more than six times that size.

As for the whistles, they made an impression on more than one young boy in the late 1980s. When famous pianist Alec Templeton visited Casper for a concert in February 1951, he apparently listened closely to the tones.

The Casper Star-Tribune community column reported the next day that Templeton sat in a Casper home remarking about the sounds.

“He said he was thinking of writing a ‘Symphony to an Oil Refinery,’” the paper reported Feb. 16, 1951. “Sometime later, he went back to the piano and played an improvisation in which the refinery whistles could be plainly discerned.”

On Monday, Dec. 28, 1953, the whistles sounded an alarm as they often did when a refinery fire broke out and the company’s fire crew were called in. The Star-Tribune reported that day that, “Standard Oil Refinery whistles barely heard above the whistle of the wind in Casper early Monday signaled a small fire atop the clay-burner building at the plant just west of the city. … There were no injuries and damages reportedly were slight.”

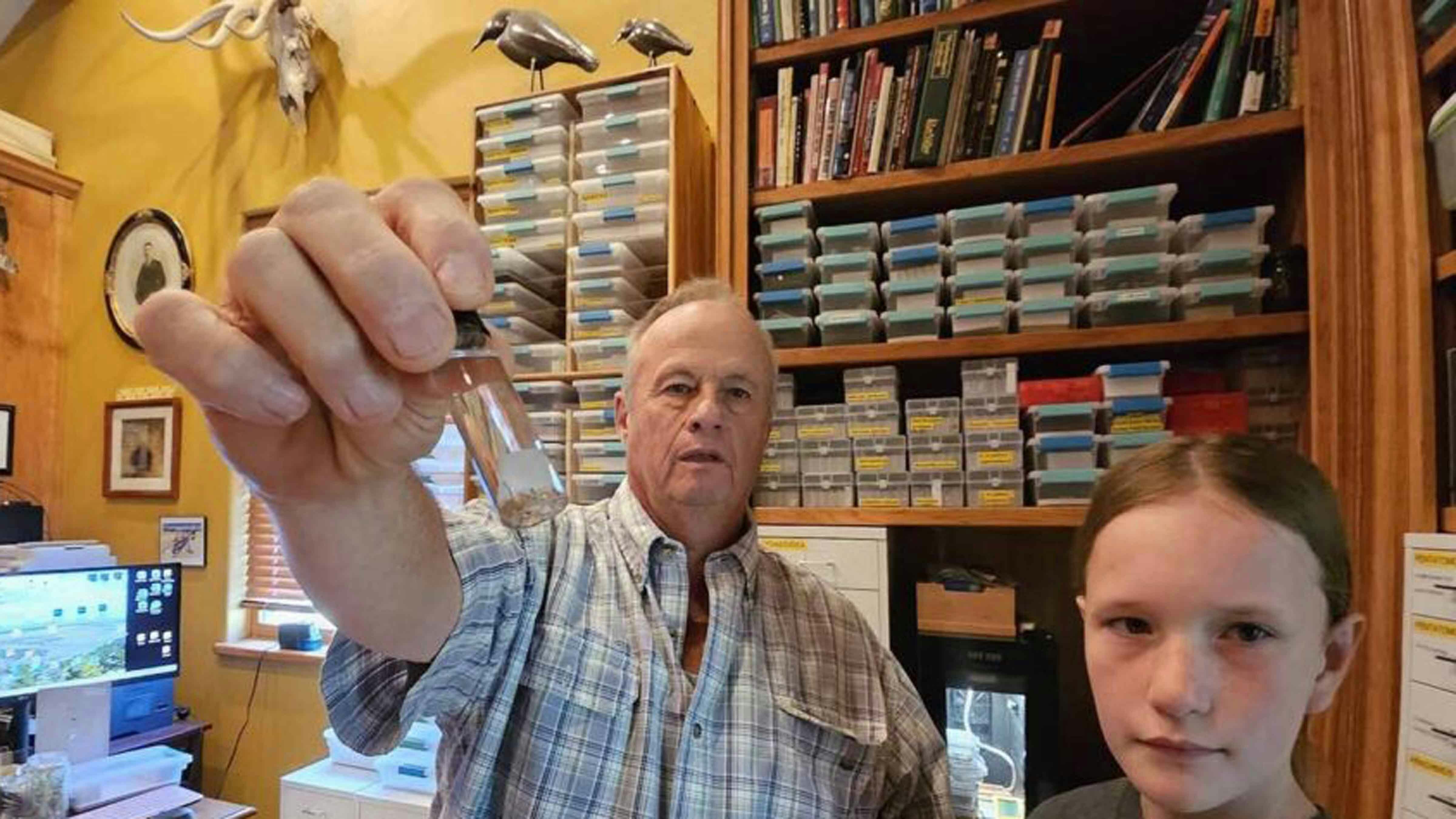

Kenneth Goehring, who now lives in the Jackson area and works as an accountant, has one of those whistles — the middle whistle. He has been looking for the other two, so far without success. But he hopes one day to gather them all and re-create that sound that tickled the ears of Templeton and raised alarms.

Kenneth’s dad, Dennis Goehring, still lives in Casper and remembers the refinery well. He worked there from 1984 through the end of production in December 1991 and stayed to helped shut it down.

He was the last operational employee to leave the plant in 1992.

Steam-Fueled Sound

Dennis Goehring said he started out on the loading docks in 1984, then moved to the boiler house and to the “cat cracker,” or catalytic cracking tower. It was in the boiler house where the whistles were mounted. There was a handle there that was pulled to send steam through the brass interior of the whistles.

“Usually, the inside operator at the boiler house blew it,” Dennis Goehring said. “Either that or your chief. It depended on who was working and if they wanted to do it or not. It was not an assigned thing, it was just whoever happened to be in there in the control room.”

Dennis Goehring said he and another employee were the last two operators to leave the refinery when it finally closed in April 1992. The other operator left the day before Goehring did. Only management would remain to oversee dismantling of various components.

“I asked the boss if I could take the whistles and he just said, ‘Go ahead,’ because they were just going to get trashed,” Dennis Goehring said. “So, I grabbed the whistles.”

The other employee, Dale Sparks, took the smaller whistle, and Dennis Goehring said he took the other two and gave the largest whistle to a woman whose father once worked at the refinery. Dennis Goehring let his son, Kenneth, have the one he kept.

“And we’ve always been wanting to hook it up to some air and try and get it to blow again,” Dennis Goehring said. “We just haven’t done it.”

Now, The Search

Kenneth Goehring said that remains his goal, but he hopes to reconnect with those who have the other two whistles and sound them all together. Attempts to contact members of the families that received the other two have been unsuccessful.

Early in the refinery’s history, Dennis Goehring said the whistles would sound for more than lunch. There were different sounds and signals that would be used to warn refinery staff of a fire or other emergencies.

“They quit doing that because we all had radios by the time I started out there,” he said. “I think we blew them a couple of times for fires.”

Dennis Goehring said the whistles were very loud and could easily be heard across the city. In the control room it was important to have hearing protection when the blasts were made. He said he considered blowing the whistle just part of his job.

And it was Dennis Goehring who was in the control room with two others the day the steam plant was scheduled to shut down — so they sounded them one last time.

“We blew it at noon,” he said. That day was about eight months before he finally walked off the refinery property.

Kenneth Goehring said the whistles were German-made by the Lukenheimer company and contain a lot of brass. He is hopeful the other two were not scrapped for their metal value. He said he has had conversations with Fort Caspar staff and may reach out to other historical museums in the region to see if there is interest in displaying the devices.

“My intent is to get them all working on air and getting them to blow,” he said. “They just mean quite a bit to me, and they would be a nice piece of history for the town to have.”

Contact Dale Killingbeck at dale@cowboystatedaily.com

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.