JACKSON — It could not have been too long after a teenaged J. Armand Bombardier invented the snowmobile in the 1920s that some rowdies hatched the bright idea of riding one up the side of a mountain.

To make a contest of the gravity-defying feat — called “highmarking” — was the next logical stroke of genius.

Fast-forward to this weekend as more than 300 contestants from all over the world are competing see who can go balls-to-the-wall straight up Snow King Mountain on a 1,574-foot climb called Exhibition.

Capped with an unfathomable 45-degree vertical section called Rock Garden, the aptly named double-black diamond run puts the wobble in extreme skiers’ knees and makes mincemeat out of $20,000 snowmachines every March. It’s billed as the steepest ski run in North America.

The new eight-passenger Summit Gondola makes the ascent in about five minutes. The fastest sleds this weekend will make a successful climb and summit in less than 90 seconds.

Tens of thousands of spectators flock to Jackson to witness the annual World Championship Jackson Hole Snowmobile Hill Climb. This year is the 47th running of the prestigious race to the peak.

This Is Big Time

What began in 1975 as a loosely organized event of dash and daring is now an official event under the Rocky Mountain States Hill Climb Association (RMSHA) umbrella. Of all the hill-climbing events authorized by RMSHA, the annual March climb at Snow King is the crown jewel of the series.

Hill Climb is big business nowadays. Neon-clad snowmachine racers are professional representatives of their sled manufacturers and numerous sponsors. Many compete at various events around the world, including the Winter X Games.

For the top snowmobile makers — Polaris, Arctic Cat and Ski-Doo — Hill Climb is all about bragging rights. For the contestants, in addition to winning their respective classes, they want to be crowned King or Queen of the Hill when the smoke clears Sunday.

The four-day event features several classifications from the typical weekender’s sled — a 600cc stock capable of over-the-snow speeds up to 100 mph — to a modified and improved 1,000cc crotch rocket capable of torqueing out a stupendous 170 horsepower or more, creating a distinctive whistle whine that can be heard at the far end of town when these racers point their skis to the top.

The Jackson Hole Snow Devils, an all-volunteer nonprofit organization, produces the event, which is a major fundraiser. The group has donated more than $500,000 to local charities. Money from local lodging tax revenue helps fund the event.

Physics Of The Hill Climb

Recall Isaac Newton’s first law of motion: An object in motion tends to stay in motion. Nearly every contestant at this year’s World Championship Hill Climb — both professional racers and highmarking weekend hooligans — will tell you the same thing: You gotta keep moving.

“Snow King is a momentum hill,” said local regular Shad Free. The 52-year-old legend of the sport has been over the top several times, so listen up when he says, “Keep your skis up and your suspension soft.”

In 2005, Shilah Dalebout became the first woman to make it to the top. She echoes the whole propulsion notion.

“The biggest thing is keeping your momentum,” Dalebout said. “It’s so steep up there that you can’t spend any time looking where you’re gonna go.”

The rest of Newton’s law: An object in motion tends to stay in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force.

Enter Snow King Mountain. Here’s where things get unbalanced.

Shove 200 horsepower into 500 pounds of sled traveling over ruts and rocks, and a hump de bump dance is on. Riders straddle, sidesaddle and shift their weight in every way imaginable to stay aboard bucking fiberglass.

Lose momentum and another natural phenomenon of physics takes over — gravity.

Objects With Mass Attract Each Other

It is one of the fundamental forces of physics and the Hill Climb. A sled is attracted to the base of the hill, or the catch net positioned mid-hill to prevent total destruction, before it ever leaves the starting line. It’s why thousands of sledneck fans gather at the base of Jackson’s Town Hill with an eye on the jumbotron screen, cheering louder for the destructive descents than the successful summits.

Even seasoned veterans aren’t immune to forces of nature. Nathan Zollinger, 44, will forever remember Hill Climb 2005 as the scene of his most embarrassing moment.

“I tipped over on Snow King in 2005 before the first catwalk,” said the former champ who won it all in 1998. “It was a rookie mistake. I got caught sleeping.”

And they still talk about the Dennis Durmas wreck of 2003.

“Best crash I’ve ever seen,” longtime announcer Glen Gillies said of the runaway sled that was headed for the crowd below until it rammed into an old ski lift tower pole, snapping it in half on impact.

“It’s always a race against the hill, and the hill usually wins,” Durmas admitted later.

Path Of Least Resistance

In physics, objects moving through a system always take the path of least resistance. It is true for electricity, water flowing downhill and snowmobile racers heading 1,500 feet uphill. Snowmachiners know where they want to go, it just isn’t always possible.

“I choose the line of least resistance,” said Jeremy Osler, a 35-year-old Bozeman racer. “You wanna stay on the ground. If you hit something and lose your line, it’s all out the window. You do what you can.”

Like a lot of contestants, Osler prefers to walk the course the day before it opens to get a good look at the whole hill.

All sledders “glass the hill” with a spotting scope to watch other contestants. Most ride the chairlift as well to get a bird’s-eye view of the action and what obstacles they may want to avoid.

“There is a mental game; having a plan is important,” said Battle Ground, Washington’s Kyle Tapio. The 44-year-old is a multi-winner of King of Kings honors.

“Sticking to the line you pick at the bottom is important,” he said. “Seventy percent of it is staying in the groove made by other riders, but toward the top you focus on bad areas and stay away from them.”

“I always have a line in my mind. I ride the lift. I have a plan,” agreed Rick Ward, another former repeat winner of the King of the Hill title. “But it can change and go away quickly, especially with the mods chewing on it, then it pays to have a Plan B.”

Free, who has been competing in the Hill Climb for more than two decades, said, “They say, ‘There is the line, and there is the line you’re on.’ Sometimes it can be deceiving from the lift view. After 15 or 20 minutes, when you get off the lift and on your sled, the lines you saw have been taken.”

“I pick a line but I also let the sled do what it needs to do,” said Zollinger, one of the ZBroz family racing team from Utah. “The hard part about Snow King is staying out of somebody else’s mistake [hole]. It’s harder also because of the ruts and where they put the gates.”

The Ottobres are Jackson locals who ran Hill Climb for many years. Jan, wife of Tony, said the stronger guys can keep their line, but she has to go where her sled goes. Ottobre became the second woman over the top at the King when she summited in 2007.

Younger riders say they’ll leave strategy to the thinkers. It’s luck and brash that gets sledders to the top.

Local Tyler Tobin, who’s mom Heidi was a longtime chair of the Snow Devils, said his golden rule of thumb is, “When in doubt, let it eat,” referring to the time-tested practice of rooster-tailing out of trouble.

Cash Or Crash

The art of setting up the sled, or tuning it to the elevation and snow conditions, keeps crews busy for days before a race.

Most racers swear by a soft suspension, which helps the machine stay in contact with the snow, and with this year’s better-than-average snowpack on the hill most riders are opting to leave the paddles long and the hardware at home.

Screws or titanium paddle extenders are what some old-timers refer to as “grouser” and are used as a means to “snow stud” their paddle track for grip in low-snow and icy conditions.

“I hate to run screws or titanium and won’t unless I have to. It creates extra vibration and weight,” Ward said.

Weight is crucial. Racers do everything they can in the trailer to offload excess weight. Even the sled’s fuel tank is shrunk to hold less than a gallon of gas.

And if racers should lose control of their sled, it’s Hill Help to the rescue.

Snow King is not only unique for its unforgiving terrain. A legion of first responders known as “Hill Help” stand at the ready, lined along either side of the course.

When sledders look like they are in trouble or flat out crash their machines. The volunteer crew has proved invaluable to snowmobilers.

“If you see them then you are not having a good day because you are not getting to the top, but it’s nice to see a face I know and have them save $25,000 worth of sled,” Free said.

“Hill Help is the best,” Ottobre agreed. “They saved my sled in 2004. The scariest part is riding back down. I tell them, ‘Here’s my helmet, you ride it down.’”

Riders are required to carry some form of braking material — usually rubber — to be looped around the skis upon descent.

Zollinger admitted he’s had to yell to Hill Help to come and get him when he knew he was just spinning track to keep from rolling back down the hill.

And Ward? He won’t even try to save his own sled.

“I learned my lesson helping my own sled once,” he said. “That’s how I’ve been hurt in the past. I owe them many thanks over the years.”

Theory Of Relativity

Racing runs in families. Father-son teams, husband-and-wife teams, and brother-sister combos are common on the 280-member RMSHA roster.

The Zollingers (ZBroz Racing) once boasted 11 family members on the circuit in one season. This year, Nathan runs the Hill Climb in the Vintage class while youngsters Daxson, 22, and Brody, 16, represent the next generation of sled shredders.

The Zollingers are joined by the Conger family out of Colorado, the Ellingfords of Wyoming, Utah’s Rogers family, the Spencers from Idaho, and Tapios of Washington.

Braaap Pack contestants come from all over the country and Canada. They range in age from a couple of contestants in their 60s in the Master division to a handful of teenagers competing in Juniors.

The elder statesman on the circuit is 64-year-old Faron Gilbert. He is also the oldest RMSHA racer to go over the top at Snow King. The Cascade, Idaho, racer rides a Ski-Doo.

The future of the sport belongs to youngsters like 20-year-old Dylan Hart, “the Flyin’ Hawaiian” out of Lolo, Montana, and the Thomases — Tanner, 21, and Cole, 22 — from Afton, Wyoming.

“Cole is one of those guys that rides on the edge of out-of-control. He’s fun to watch,” Hill Climb livestream announcer Kenny Eggleston said while covering the 2024 Hill Climb on Friday.

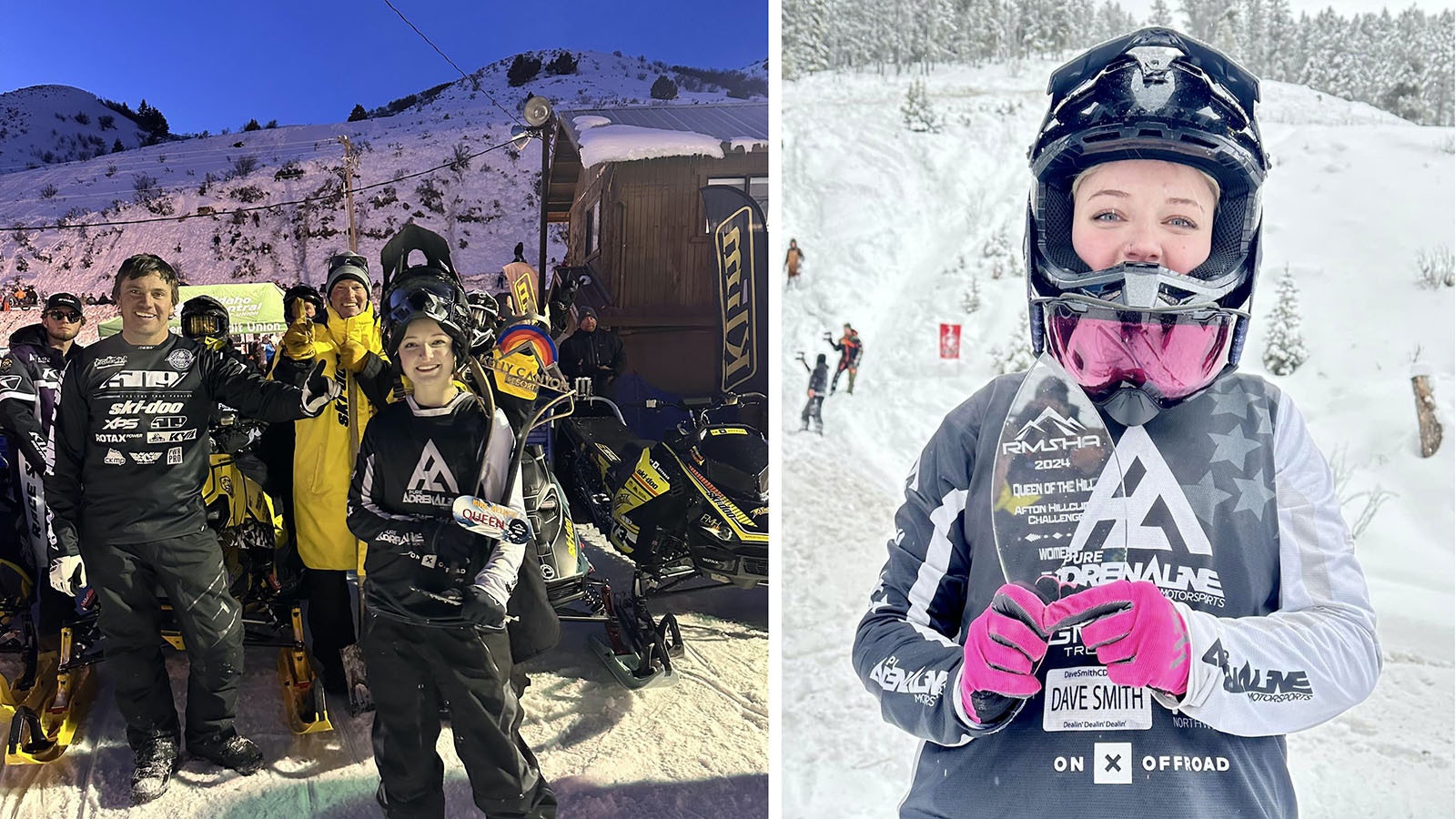

For the ladies, keep an eye on hotshot Brooke Long. The 19-year-old from a family of racers in Spirit Lake, Idaho, took Queen of Kelly Canyon honors earlier this month at the inaugural hill climb in Ririe, Idaho, as well as queen at the 2024 Simplot Afton Hill Climb.

“She is just such a sweetheart,” Eggleston said.

Everyone with a bib number will be chasing Keith Curtis and his Polaris. The 36-year-old out of Dillon, Montana, is gunning for a record ninth King of Kings title at the World Championship Hill Climb.

Jake Nichols can be reached at: Jake@CowboyStateDaily.com

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.