At 352 feet long, the Big Island Bridge, built in 1909, opened up one of the last sections of the United States for homesteading by crossing the Green River in Sweetwater County.

It was a large investment for the state and was the longest road bridge in Wyoming at the time it was built.

But the hopeful homesteaders who crossed it with their teams and wagons soon learned that the sandy soil in that part of southwest Wyoming wouldn’t hold a ditch in place or grow any crops that would turn a profit. By 1920, the bridge and the area it opened up were mostly abandoned.

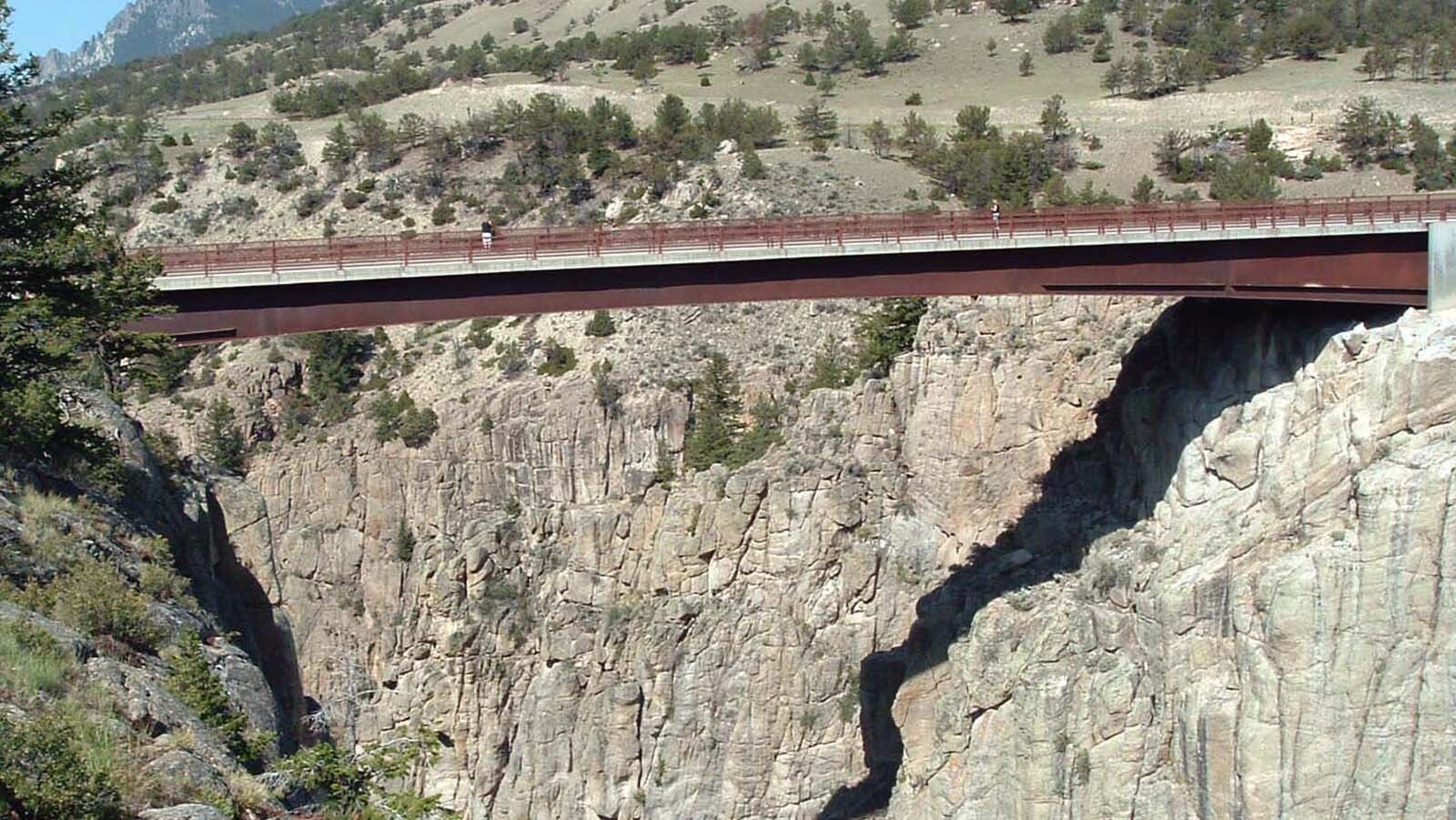

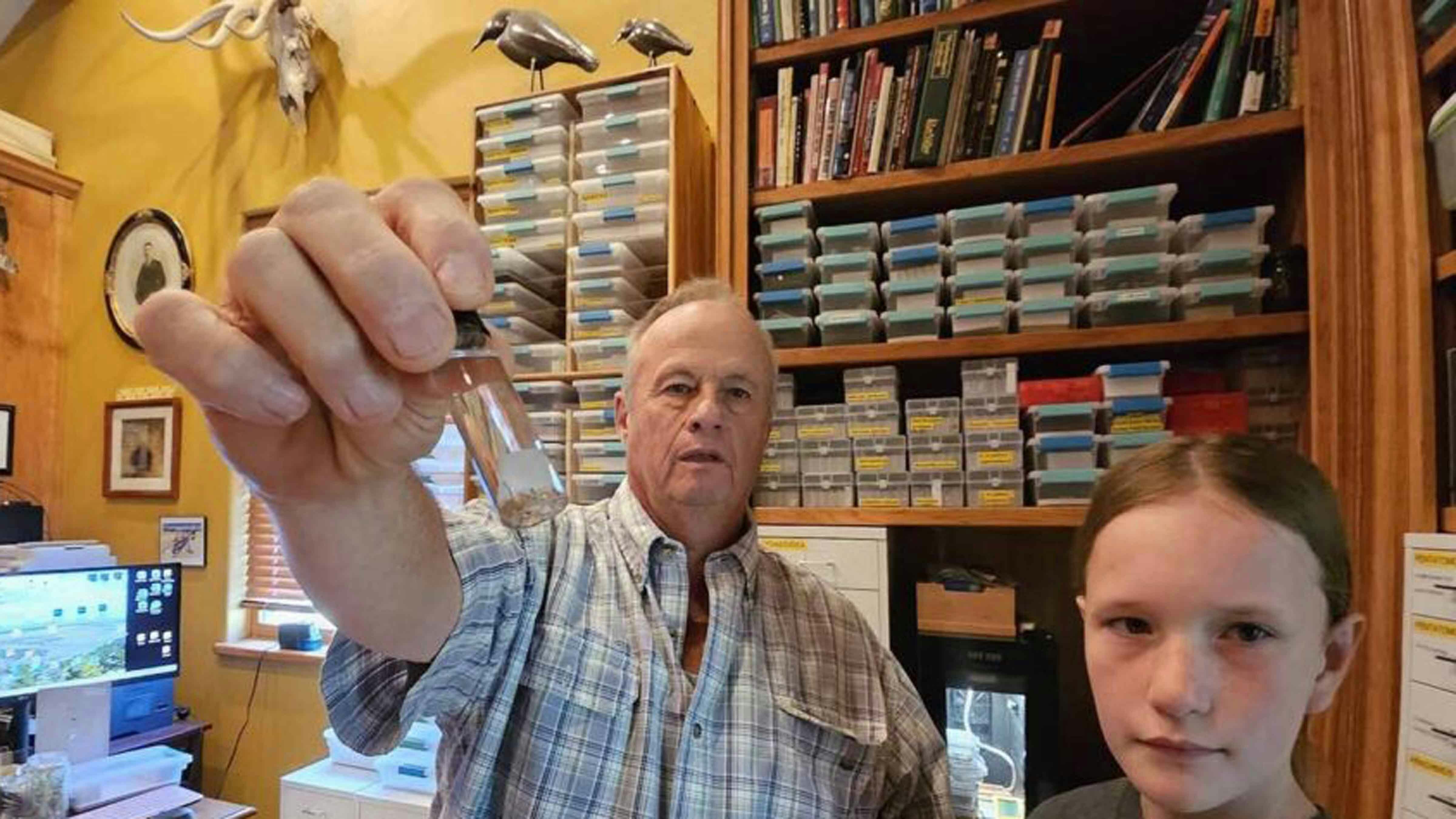

Wyoming is the home of numerous bridges with historic significance, and a self-professed “bridge nerd” named John Bernhisel is documenting the stories behind nearly every one of them. Big Island Bridge is one of his favorites.

“To me, bridges have souls,” Bernhisel told Cowboy State Daily. “They represent historic moments of human ambition. When I hiked the 2 miles in the mud a few years ago to see this bridge, it had long since been abandoned. I stood there in the rain and listened to the stories it told me.”

On A Mission

Bernhisel grew up in the Bay Area of California in the shadow of one of America’s most famous bridges, the Golden Gate. He maintains Wikipedia pages on several Wyoming bridges and spends his summers traveling around the state visiting and photographing what’s left of many of Wyoming’s historic bridges.

He also frequents places where Native Americans crossed Wyoming rivers. He is interested in writing a book about Wyoming pathways once he retires from teaching science and physics to high school students in Big Horn County.

In 1985, 40 Wyoming bridges of historical significance were located by the National Register of Historic Places, Bernhisel said. Of those 40, only 15 still exist. Five are abandoned and still in place, two have been preserved by moving to a new location and eight are still in use.

There are only three that Bernhisel has yet to visit. His goal is to document all of the bridges that are still standing and identify and photograph the exact sites of those bridges that no longer exist.

Connecting A Country

“I grew up in California not far from the Golden Gate Bridge and I probably ran across it hundreds of times,” he said. “I’ve always been interested in engineering, and as my hair has gotten grayer, I’ve started to appreciate all of the history associated with bridges and to realize that maybe we haven’t documented that history as well as we could have.”

Consider for instance, the Dale Creek Crossing, located about 20 miles southeast of Laramie. Building a structure over the Dale Creek Gorge that could support trains was one of the biggest challenges the transcontinental railroad faced.

This bridge or trestle was originally made of wood and is located at the highest elevation point, 8,247 feet, on the Union Pacific route of the transcontinental railroad. At 720 feet long and 150 feet tall, it was one of the largest train bridges in the world when it was built in 1868.

It swayed in the Wyoming wind on April 23, 1868, as the first train ambled across at what engineers deemed a safe speed of 4 mph. After that first crossing, carpenters were immediately called in to shore up the structure, and two of them fell to their deaths while working on the trestle.

In 1876, the wooden trestle over the Dale Creek Gorge was replaced with an iron structure built in Chicago, Illinois. Then in 1901, the bridge was abandoned and dismantled by Union Pacific when the rail line was rerouted over Sherman Hill, shortening the route by 30 miles.

Bernhisel said the Dale Creek Crossing is significant for its association with the establishment of the transcontinental railroad which opened the West for settlement following the Civil War.

Nearly Lost To Time

What’s left of the bridge is on private land today.

“The old granite foundations are all that is left today,” he said. “You can stand at one side and imagine how massive it was. It’s a great piece of history and the transcontinental railroad would not have existed without it.”

As part of the process of nerding out over old bridges, Bernhisel said he spends time searching Google Maps for old trestles and then finding a hiking or mountain bike trail that will lead him somewhere close to an old structure or what’s left of it.

“There are some old black-and-white photographs, but not really much more than that in the public domain of what some of these old bridges look like,” he said. “It’s become a hobby of mine to track them down.”

Yellowstone Bridges

Bernhisel said not everyone who comes to Wyoming and Yellowstone National Park comes to see Old Faithful. The park also has some historic bridges that have peaked Bernhisel’s attention. He said the iconic Fishing Bridge near Yellowstone Lake is an engineering marvel.

“For the people who just drive across it, you can’t really even tell it’s a bridge,” he said. “But when you get under it and take a look at the craftsmanship, it’s amazing that they could take that wood and pound it into the ground and make it last 120 years.”

Another historic bridge Bernhisel likes to talk about is the Fort Steele Bridge between Laramie and Rawlins. He said it was built in 1869 as part of the transcontinental railroad and had to be guarded while under construction to keep the Native Americans from burning it down.

“It’s a piece of history that is slowly going away,” he said. “I’m not saying we have to preserve all these old wood bridges, but they are part of Wyoming tourism that we are not taking advantage of.”

Information about all the Wyoming historic bridges Bernhisel has documented can be found online here.