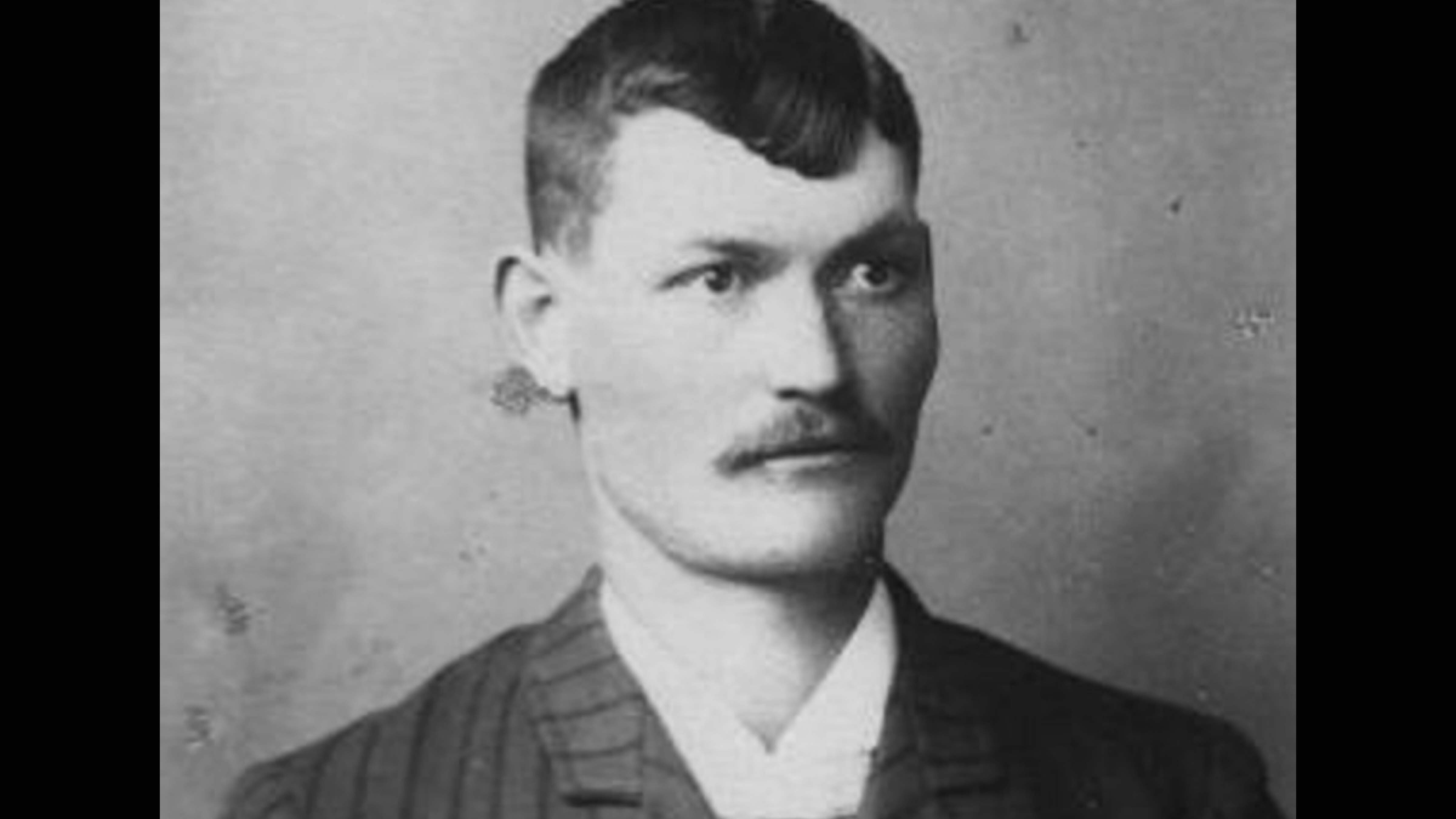

Nate Champion (1857-1892) was born Sept. 29, 1857, in Leander, Texas, the son of John and Nomi Champion. His family was big by any standard: he had 18 brothers and sisters. At one time his father was the Sheriff in Williamson County Texas and his aunt was a cattle woman and became the first postmaster in Cedar Park, Texas.

The most well-known cattle trail used to trail beef from Texas to Kansas passed near the Champion home. This trail, named for Jesse Chisholm, would be in use for nearly 20 years, from 1867 to 1885. Along the route cowboys moved great herds of formerly wild Texas cattle to markets in Abilene and other Kansas railroad towns.

Nate was 14 when his Aunt Hattie Cluck traveled the trail in 1871 taking a herd of cattle to the stockyards in Abilene. With the profits from the drive Harriet (Aunt Hattie) and George Cluck purchased the land that is now Cedar Park, Texas. The trip his aunt took no doubt inspired him and Champion soon began chasing cattle himself, becoming a cowboy and migrating north to Wyoming where he worked for several outfits before beginning his own ranching operation. In 1891, he and his partner Ross Gilbertson had their own herd. Nate would look after the herd while "Ross worked for wages" as Nate wrote in a letter in 1891.

By early April 1892, Champion had just paid off eight packhorse rigs and had nearly 200 head of cattle in his herd. His efforts to establish a ranch, however, had placed him in the cross-hairs of the powerful cattlemen in Wyoming. He was at the KC Ranch (which gave the town of Kaycee its name) on April 9, 1892.

Four days earlier, on April 5, 1892, a train rolled into Casper from Cheyenne. Known as “The Invasion Special,” the train had three stockcars filled with horses, a car filled with supplies and baggage, a flat car holding three Studebaker wagons, plus a passenger car where gun-towing men from Wyoming, Texas, and Idaho had ridden – and made plans – on the journey north. Once in Casper, the men using horses and their wagons, organized to travel north toward Buffalo. They set in motion a series of events that became known as the Johnson County Invasion, and which is sometimes called the Johnson County War.

The organizers of the invasion had drawn up a list of men suspected of being rustlers, whom they intended to kill. Nate Champion was one of the men on it. He was at a KC Ranch house when the cattlemen surrounded the place. Two men with Champion slipped through the cordon of cattlemen and their hired guns, escaping the brewing conflict.

Shortly after breakfast Nate Ray left the cabin and the invading force shot him. He fled back into the structure where Champion tended Ray’s wounds until he died later in the day.

Champion knew he was in a tight spot, but he recorded what was happening in a small notebook: “Boys, I feel pretty lonesome just now. I wish there was someone here with me so we could watch all sides at once. They may fool around until I get a good shot before they leave.” (Champion Journal, published in the Cheyenne Daily Leader, April 14, 1892, and in the Chicago Herald, April 16, 1892.)

Late in the afternoon Jack Flagg, a friend of Champion, and Flagg’s stepson Alonza Taylor, drove a wagon past the ranch house. Seeing the invaders, the two fled toward Buffalo, where they would spread the alarm about the attack at the KC Ranch.

Champion recorded in his journal: “Well, they have just got through shelling the house again like hail. I heard them splitting wood. I guess they are going to fire the house tonight. I think I will make a break when night comes, if alive.” Then later: “Shooting again. I think they will fire the house this time.”

Outside the invaders filled a wagon with hay and set it on fire before pushing it into the ranch cabin.

Champion wrote a final message: “It’s not night yet. The house is all fired. Goodbye, boys, if I never see you again.”

Major Frank Wolcott, one of the well-known cattlemen who helped organize the invasion, took Champion’s little notebook after the man died in a hail of gunfire as he fled the burning cabin. In a great service to the historical record, but an odd circumstance of the day, Wolcott gave Champion’s notebook to Chicago Herald reporter Sam Clover, who accompanied the cattlemen and their hired gunmen. Then, in another oddity, the journal was published first in the Cheyenne Daily Leader, on April 14, 1892, and two days later in the Chicago Herald.

After killing Champion, the cattlemen and their force rode north toward Buffalo where they expected to find the rest of the men on their dead list. Before reaching their destination, they were met by Sheriff Frank Canton and a group of Johnson County men who soon had the invaders pinned down at the TA Ranch.

It took intervention by Wyoming Governor Amos Barber, Senators Frances E. Warren and Joseph M. Carey, and President Benjamin Harrison, to diffuse the situation. Harrison issued an order that led troops from Fort McKinney to ride to the TA Ranch and take custody of the Invaders.

Although charges were filed for the killing of Ray and Champion, no jury was seated to hear the case and on January 18, 1893, officials dropped all charges; none of the invaders ever faced prosecution.

Since that time many songs have been written, movies made, and stories told about Nate Champion. He is remembered with a bronze sculpted by D. Michael Thomas that stands in front of the Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum in Buffalo. And in 2014 he was one of the first men inducted into the Wyoming Cowboy Hall of Fame.