Rockhounding was a way of life for Carol Cheatham and her five siblings as they grew up in the Big Horn Basin in the 1950s and 1960s.

Their childhood pastime has been commemorated forever in textbooks and museums – because their father, Ray Cheatham, was the man who discovered what was at the time the largest ammonite fossil ever found in North America.

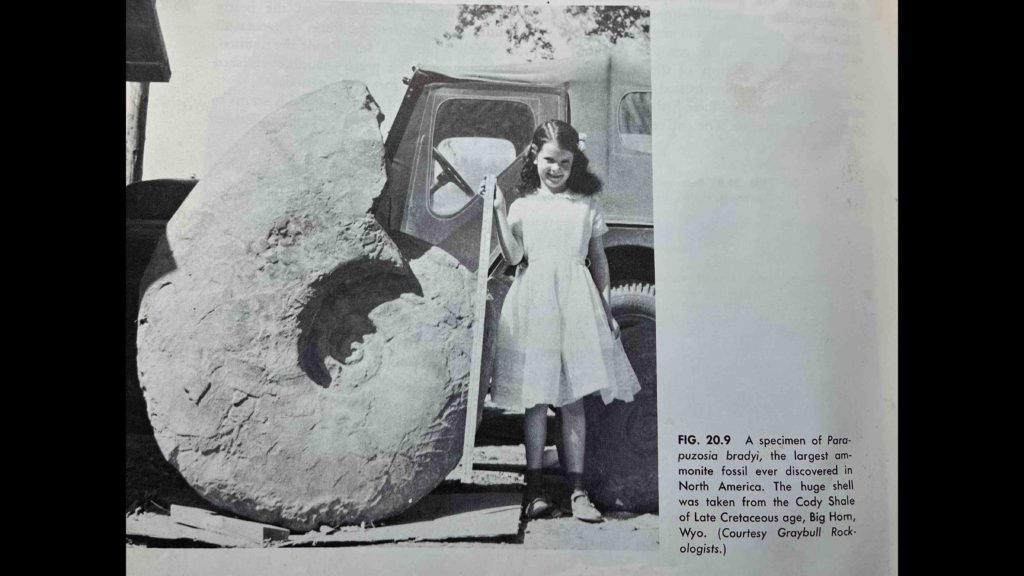

“(There’s a) college Geology textbook in which my picture appeared with the ammonite,” Cheatham told Cowboy State Daily. “It was actually used in classes taken at (Brigham Young University) by (brother) Bob and my older sister, Barbara.”

The Parpuzosia bradyi was found in Big Horn County by Raymond Cheatham in the early 1960s, and excavated piece-by-piece by the Greybull Rock Club. The giant fossil, at 55 inches high, was taller than 5-year-old Carol was at the time the artifact was found.

“The ammonite was found in what’s called the Cody shale formation,” said Carol’s brother Bob, who pursued a geology degree at BYU because of the love for rocks instilled in him by his parents. “It’s Cretaceous in age, it’s (about) 100 million years old.”

Ammonite fossils have a distinctive coil shape. Between 66 million and 450 million years ago, they were the shells that protected ocean-dwelling squids.

Ammonites are not uncommon in Wyoming. Earlier in May, amateur rockhounds scouting in Powder River in Natrona County found a fossilized ammonite 19 inches across and 16 inches high.

Carol said the huge artifact her family found was possibly the most impressive find that she, her parents and her siblings were ever a part of collecting – but then again, for the Cheatham family in the 1950s and 1960s, rockhounding was a part of their life.

“It was an adventure every weekend going looking for fossils, and going up to the mountains and learning about the land we were living on,” she said. “I thought it was a very important way to grow up.”

Cheatham said the entire family would go on to become members of the Greybull Rock Club, which her parents helped found.

“The Greybull Rock Club (would) five times a year go out on field trips and bring things in,” said Bob. “And they also went to see Indian petroglyphs and things like that.”

Bob and Carol recalled fondly how their father, who was a surveyor for the company which operated the bentonite plant in Greybull, learned about geology while on the job.

“His job was to survey the plot for the open pit mines, where they withdraw the bentonite,” said Bob. “So the geologist and him became very close friends. And they would survey their plot, then they would go out and hunt for other areas where bentonite might be – but this geologist taught dad about different geological formations, and he knew what was there as far as fossils or other things.”

According to Carol, her father was out surveying when he made the monumental discovery.

“He was on the job when he found it,” she said. “And he actually couldn’t do anything about it. He knew where it was, and then he went back to town and told another person interested in geology about it, and that person went out and retrieved it.”

Carol said the huge ammonite was taken out of the ground in pieces, and the rock club put the fossil together in the display case it currently rests in at the Greybull museum.

“Dad built the frame that goes around it,” Bob added. “It took them a while to get that ammonite from where it was, it might have taken a year.”

Carol noted that in part because of their parents’ love for science, every one of the Cheatham siblings went on to get college degrees, two of them earning their PhD’s. Carol herself is a developmental cognitive neuroscientist on the faculty at the psychology and neuroscience department at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

“Mom and dad only had high school educations,” Carol said. “But all six of us went to college. I think their love of science, and all things education and all things books – we had a house full of books.”

The Cheatham family’s rockhounding legacy can still be found at the Greybull Museum, proudly displayed as an example of the rich fossil record that lies under the sands of the Big Horn Basin.

“Wyoming is a great place to study geology,” said Bob. “In fact, the Big Horn basin is so great that (colleges bring students) into the area to study the geology. And it’s because, in the Big Horn basin, you can actually see the geology.”

“With every heavy rain, more fossils wash up,” Carol pointed out.