Bostock v. Clayton County, the Supreme Court’s latest adventure in legislating, has already seen enough compelling analysis to raise some troubling questions. Here’s a quick overview.

Justice Kavanaugh’s dissent showed that the majority did not interpret Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Rather the Court rewrote Title VII, inserting language that multiple previous congresses decidedly rejected. This is a “transgression of the Constitution’s separation of powers,” he wrote.

The dissenting opinion of Justices Alito and Thomas was stronger still. “There is only one word for what the Court has done today: legislation.” It emphasizes that our elected representatives are currently considering H.R. 5, the so-called “Equality Act,” which would amend the very law that Bostock rewrote. But rather than let the elected legislators vote, six unelected justices disenfranchised 360 million votes cast in three separate elections.

The majority not only arrogated this task to itself, but did it in the laziest way possible. It rewrote a single line of the U.S. Code that would affect 167 different provisions of federal law—but refused to reconcile the contradictions it created.

Among the 167 questions left unanswered are whether men’s access to women’s dressing rooms and sports leagues will be mandated. Whether female students and women escaping from domestic violence will be forced to share dorm rooms and living quarters with men, it didn’t say.

Patients will sue doctors both for removing healthy sex organs and for refusing to remove healthy sex organs. The majority could not be bothered to tell doctors which side will win. These, “are questions for future cases,” it said.

The evasive majority thus refused to commit itself to the logic of its own opinion—for good reason. The opinion’s fatal flaw is an equivocation in the opening paragraph.

Gorsuch wrote, “An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex. Sex plays a necessary and undisguisable role in the decision, exactly what Title VII forbids.”

This framing of the question assumes that a man’s right to present as a woman is hindered by the unalterable fact of his sex—he can’t help it if he’s a man. Therefore, the Court must come to the rescue and forbid an employer from taking his sex into account.

Gorsuch’s foundational claim that sex is unalterable is heretical to gender theorists. When J.K. Rowling recently said that, “sex is determined by biology,” the outrage mob wanted her canceled.

How Justices Kagan, Breyer, Ginsburg and Sotomayor could have signed onto this opinion without incurring the wrath of the same mob should be puzzling.

But, of course, no one is surprised. In our brave, new world, logical inconsistencies are par for the course. In fact, Gorsuch is not the first to opine that “sex discrimination” includes any legal recognition of the unalterable fact of sex.

The theory has been around since 1975, when he was in third grade. Moreover, his fellow Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, has spent 45 years arguing against it!

Gorsuch asserts that this self-contradictory opinion is driven by strict and principled “textualism.” But he never once uses the word, “originalism.” It would be better described as “pre-textualism,” because he has no intention of determining the original meaning of the text.

First, neither “homosexual,” nor “transsexual” is, in fact, in the text. Second, multiple legislators over the course of 45 years have proposed changes in the text precisely because the text does not address homosexuality and transsexuality. Third, his concurring justices, Kagan, Breyer, Ginsburg and Sotomayor, have a long and proud history of defying textualism at every turn.

I am not pointing out anything that the majority didn’t already know. They are extremely smart and capable lawyers. Doubtless, Alito, Thomas and Kavanaugh have been reminding them of the logical, constitutional and legal problems for the past several months.

They knew full well that their opinion would require decades of litigation costing millions. They knew that countless doctors, churches, businesses and charities would be sued into oblivion.

They also could have explicitly limited Gorsuch’s theory to Title VII alone. But the majority both refused to rule out any of the 167 new applications, while also refusing to admit that they would all logically follow.

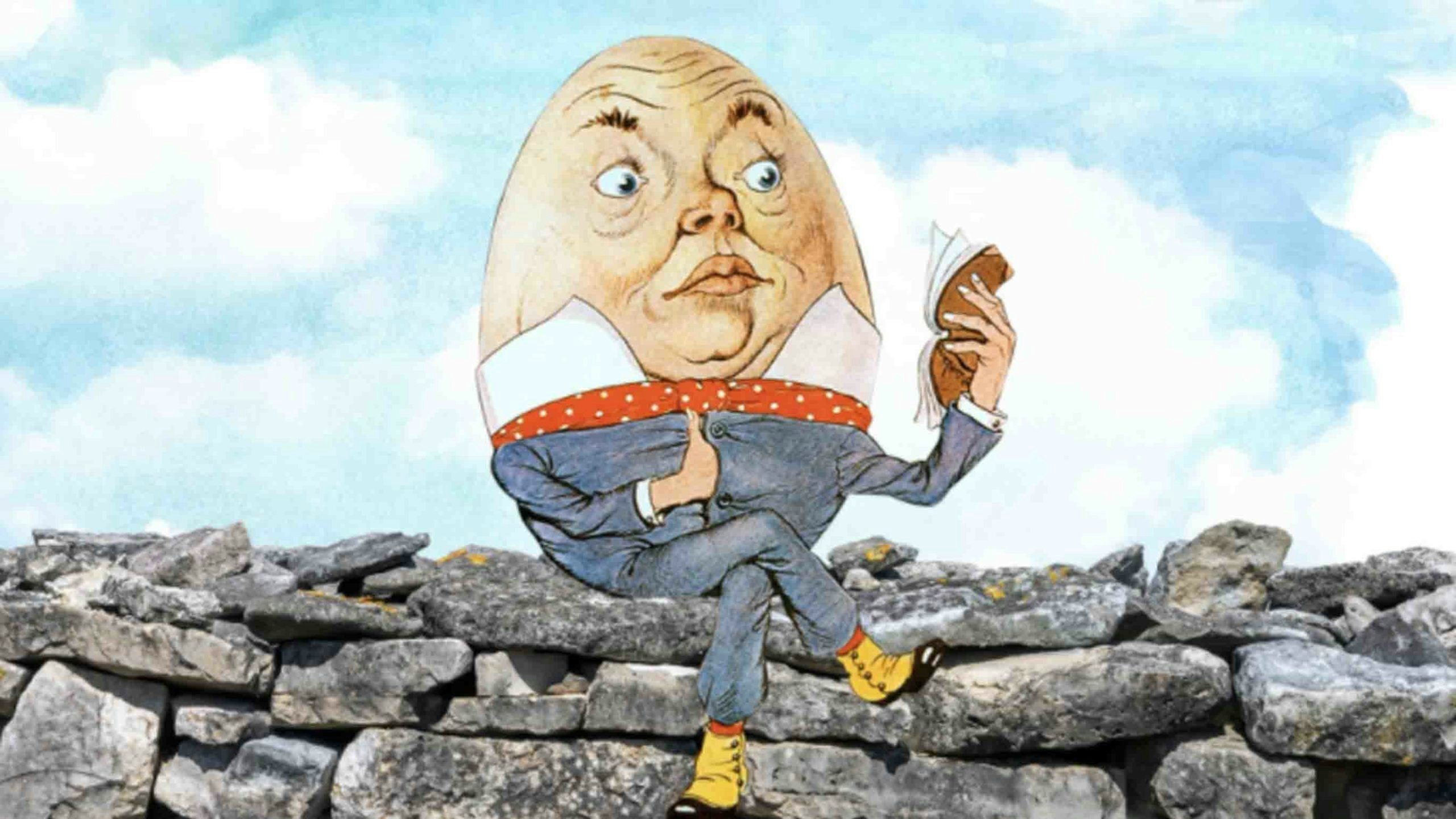

This is now a Humpty Dumpty court. “When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” “The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

The Bostock majority is now that master. That is all.